Overview

This tutorial demonstrates how to specify the models used in a Bayesian “combined-evidence” phylogenetic analysis of extant and fossil species, combining morphological and molecular data as well as fossil occurrence data from the fossil record [e.g., Ronquist et al. (2012), Zhang et al. (2016), Gavryushkina et al. (2017)]. We begin with a concise to the models used in this analysis, followed by a detailed example analysis in demonstrating how to apply these models in RevBayes (Höhna et al. 2017) and use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to estimate the posterior distribution of dated phylogenies for data collected from living and fossil bears (family Ursidae).

Introduction

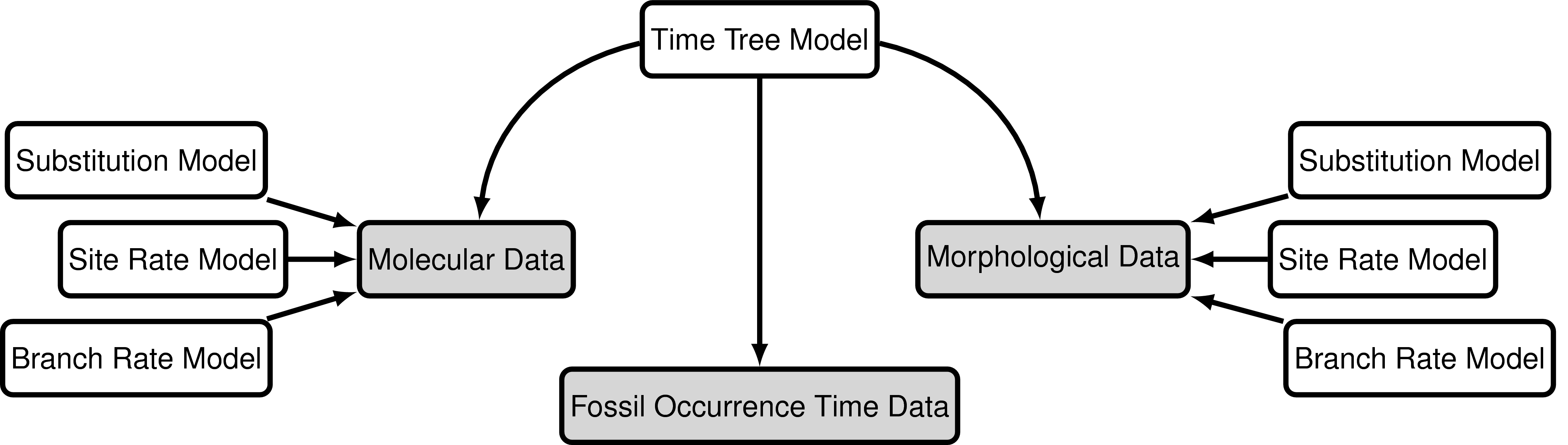

The “combined-evidence” analysis described in this tutorial uses a probabilistic graphical model (Höhna et al. 2014) integrating three separate likelihood components or data partitions (): one for molecular data (), one for morphological data (), and one for fossil age data (). In addition, all likelihood components are conditioned on a tree topology with divergence times which is modeled according to a separate prior component ().

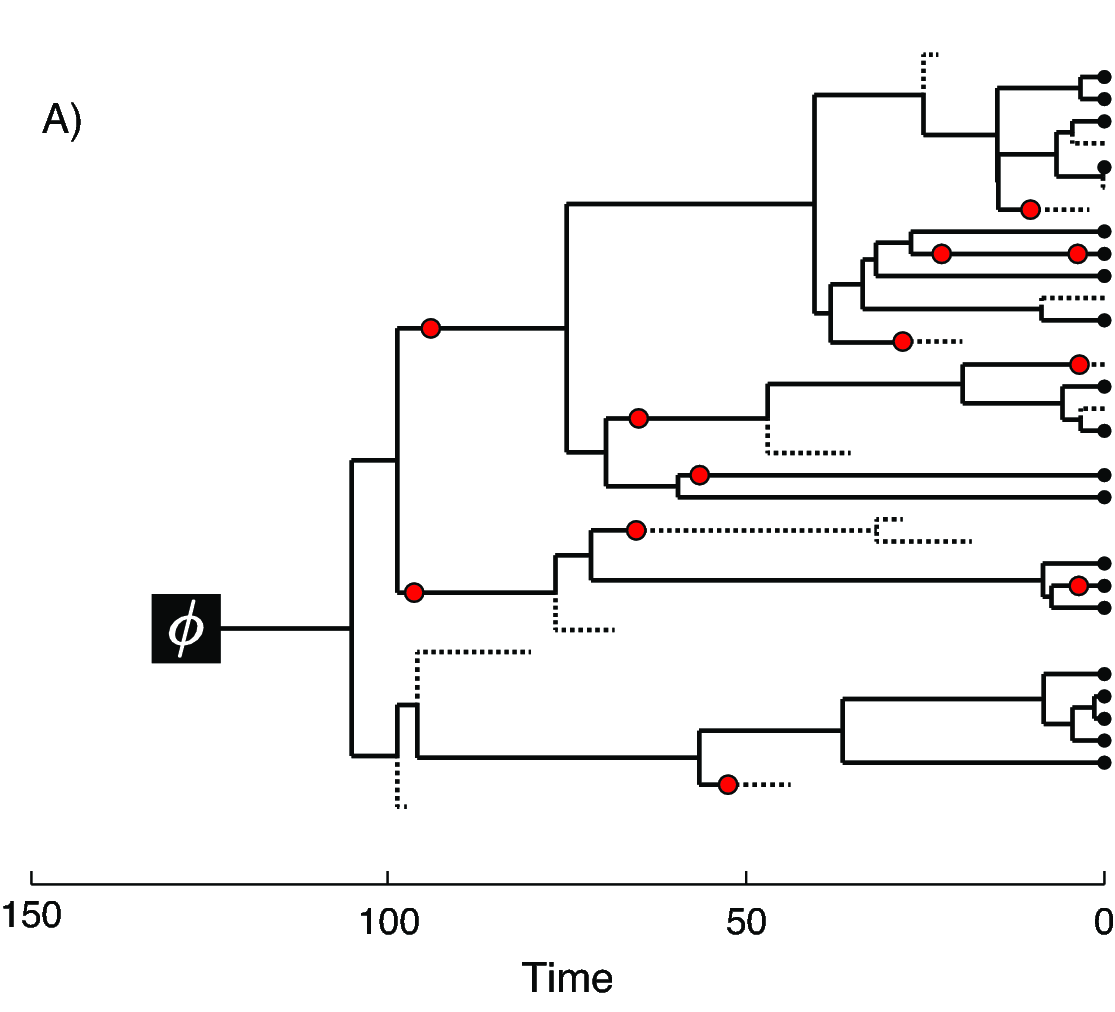

In we provide an example of the type of tree estimated from a total-evidence analysis. This example shows the complete tree (A) and the sampled or reconstructed tree (B). Importantly, we are interested in estimating the topology, divergence times and fossil sample times of the reconstructed tree (B). We will describe the distinction between these two trees in .

Lineage Diversification and Sampling

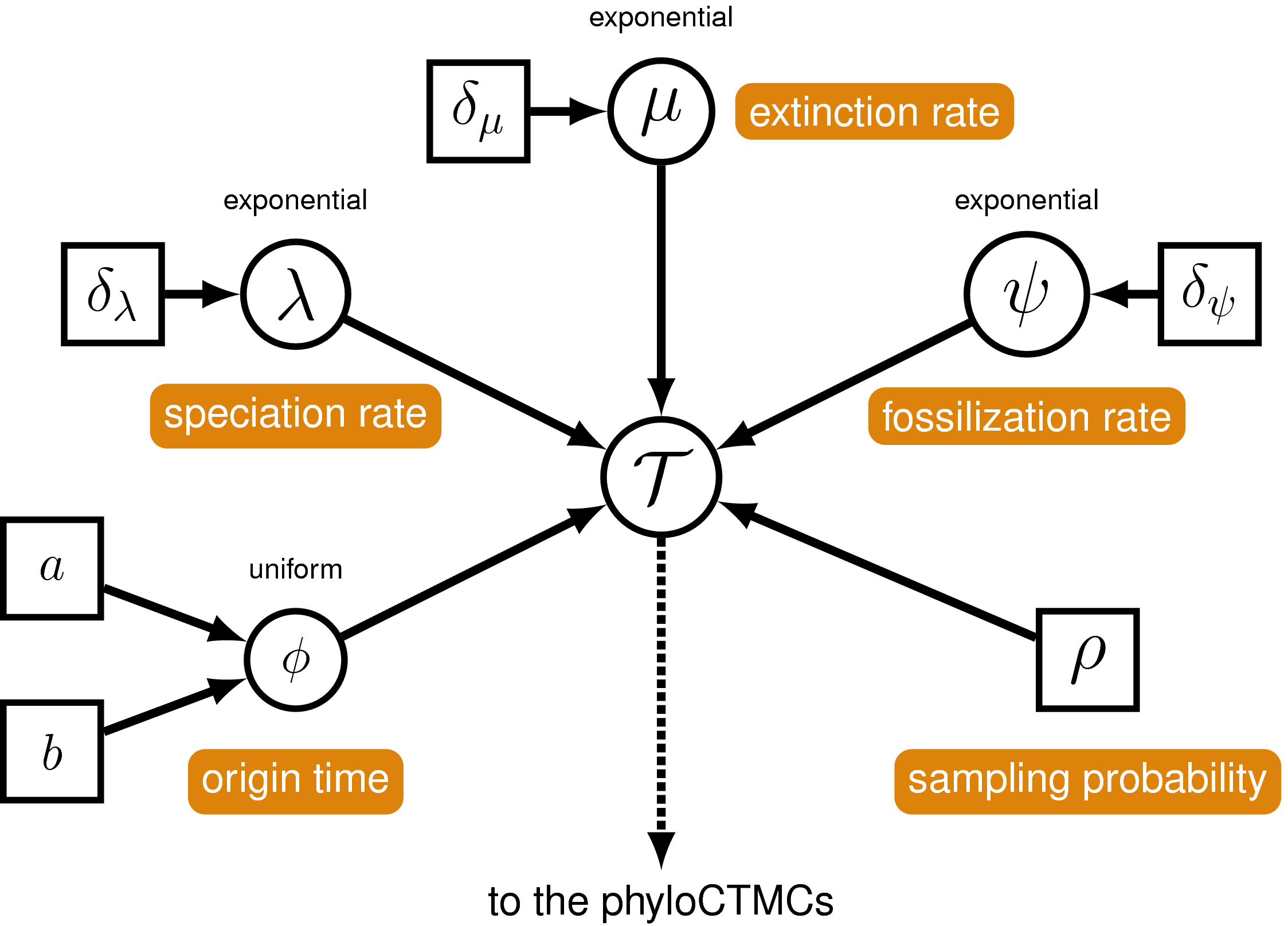

The joint prior distribution on tree topologies and divergence times of living and extinct species used in this tutorial is described by the fossilized birth-death (FBD) process (Stadler 2010; Heath et al. 2014). This model simply treats the fossil observations as part of the process governing the tree topology and branch times (the node in ). The fossilized birth-death process provides a model for the distribution of speciation times, tree topology, and lineage samples before the present (e.g., non-contemporaneous samples like fossils or viruses). This type of tree is shown in . Note that this model can be used with or without character data for the historical samples. Thus, it provides a reasonable prior distribution for analyses combining morphological or DNA data for both extant and fossil taxa—i.e., the so-called “total-evidence” approaches described by Ronquist et al. (2012) and extended by Zhang et al. (2016) and Gavryushkina et al. (2017). When matrices of discrete morphological characters for both living and fossil species are unavailable, the fossilized birth-death model imposes a time structure on the tree by marginalizing over all possible attachment points for the fossils on the extant tree (Heath et al. 2014), therefore, some prior knowledge of phylogenetic relationships is important.

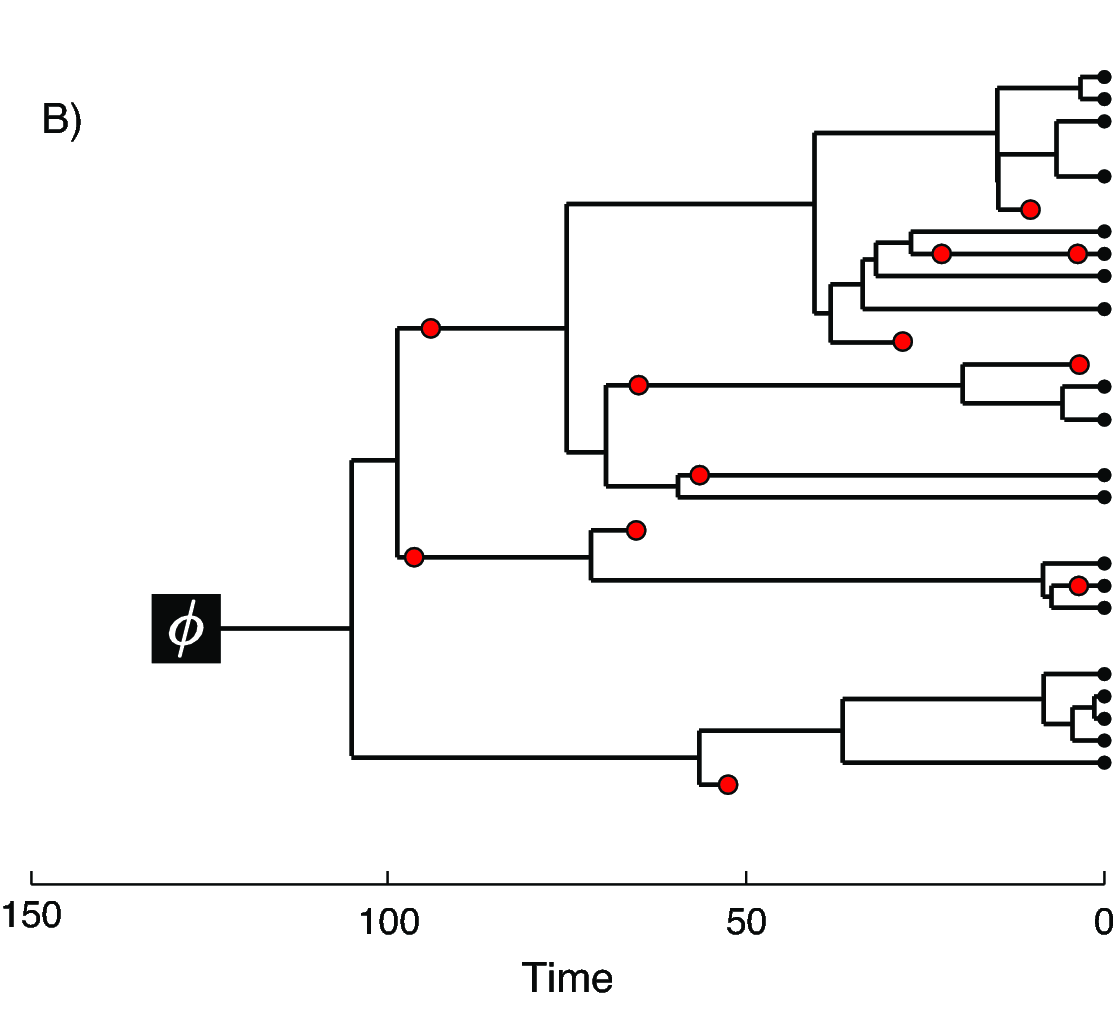

The FBD model () describes the probability of the tree and fossils conditional on the birth-death parameters: $f[\mathcal{T} \mid \lambda, \mu, \rho, \psi, \phi]$, where $\mathcal{T}$ denotes the tree topology, divergence times fossil occurrence times and the times at which the fossils attach to the tree. The birth-death parameters $\lambda$ and $\mu$ denote the speciation and extinction rates, respectively. The “fossilization rate” or “fossil recovery rate” is denoted $\psi$ and describes the rate at which fossils are sampled along lineages of the complete tree. The sampling probability parameter $\rho$ represents the probability that an extant species is sampled, and $\phi$ represents the time at which the process originated.

In the example FBD tree shown in , the diversification process originates at time $\phi$, giving rise to $n=20$ species in the present, with both sampled fossils (red circles) and extant species (black circles). All of the lineages represented in A (both solid and dotted lines) show the complete tree. This is the tree of all extant and extinct lineages generated by the process. The complete tree is distinct from the reconstructed tree (B) which is the tree representing only the lineages sampled as extant taxa or fossils. Fossil observations (red circles in ) are recovered over the lifetime of the process along the lineages of the complete tree. If a lineage does not have any descendants sampled in the present, it is lost and cannot be observed, these are the dotted lines in A. The probability must be conditioned on the origin time of the process $\phi$. The origin ($\phi$) of a birth-death process is the starting time of the stem lineage, thus this conditions on a single lineage giving rise to the tree.

An important characteristic of the FBD model is that it accounts for the probability of sampled ancestor-descendant pairs (Foote 1996). Given that fossils are sampled from lineages in the diversification process, the probability of sampling fossils that are ancestors to taxa sampled at a later date is correlated with the turnover rate ($r=\mu/\lambda$) and the fossil recovery rate ($\psi$). This feature is important, particularly for datasets with many sampled fossils. We expect a large proportion of sampled ancestors for most biologically-realistic parameter combinations in the FBD model. In the example (), several of the fossils have sampled descendants. These fossils have solid black lines leading to the present.

Incorporating Fossil Occurrence Time Uncertainty

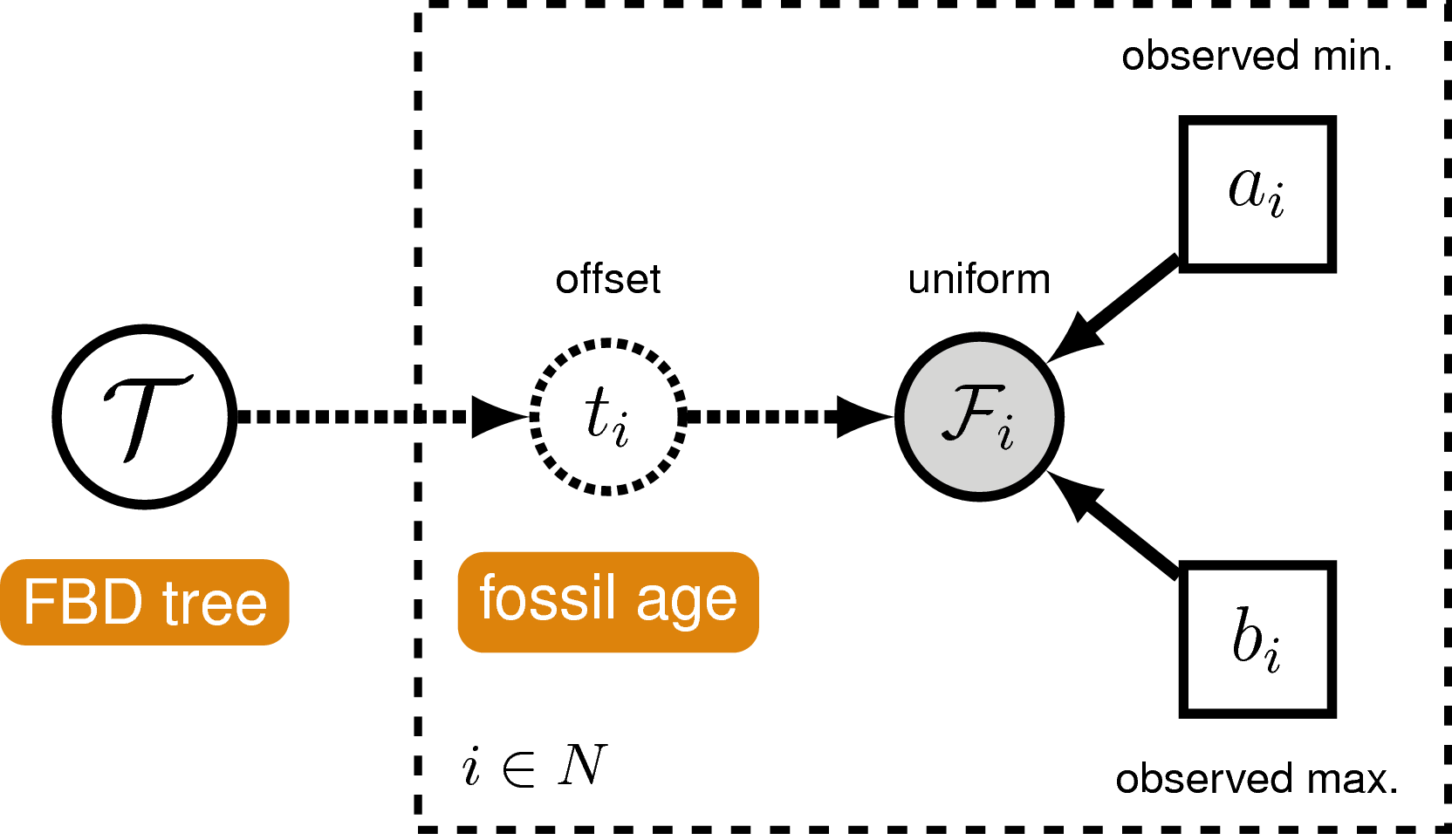

In order to account for uncertainty in the ages of our fossil species, we can incorporate intervals on the ages of our represented fossil tips. These should ideally represent specimen-level uncertainties (stemming from the imprecise dating of the geological unit from which a given fossil was collected) rather than stratigraphic ranges (i.e., the interval between the first occurrence of a given species and its last occurrence, assuming that at least two stratigraphically unique occurrences do in fact exist). We can account for such specimen-level uncertainties by assuming each fossil can occur with uniform probability anywhere within its observed interval. This is somewhat different from the typical approach to node calibration. Here, instead of treating the calibration density as an additional prior distribution on the tree, we treat it as the likelihood of our fossil data given the tree parameter. Specifically, we assume the likelihood of a particular fossil’s age uncertainty range $F_i = (a_i, b_i)$ is equal to one if the fossil’s inferred age on the tree $t_i$ falls within this interval, and zero otherwise:

\[f[F_i \mid t_i] = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } a_i < t_i < b_i\\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]In other words, we assume the likelihood is equal to one if the inferred age is consistent with the age data. We can represent this likelihood in RevBayes using a distribution that is proportional to the likelihood, i.e. non-zero when the likelihood is equal to one (). This model component represents the “Fossil Occurrence Time Data” in the modular graphical model shown in .

Once again, it is worth noting that this is not the appropriate way to model fossil data that consist of stratigraphic ranges, which represent multiple fossil specimens (each of which can further be associated with its own specimen-level uncertainty) observed at different times along a single lineage. An extension of the fossilized birth-death process that is a distribution on stratigraphic ranges was described by Stadler et al. (2018).

Nucleotide Sequence Evolution

The model component for the molecular data uses a general time-reversible model of nucleotide evolution and gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity across sites (the Substitution Model and Sites Model in ). This model of sequence evolution is covered thoroughly in the Nucleotide substitution models tutorial.

Lineage-Specific Rates of Sequence Evolution

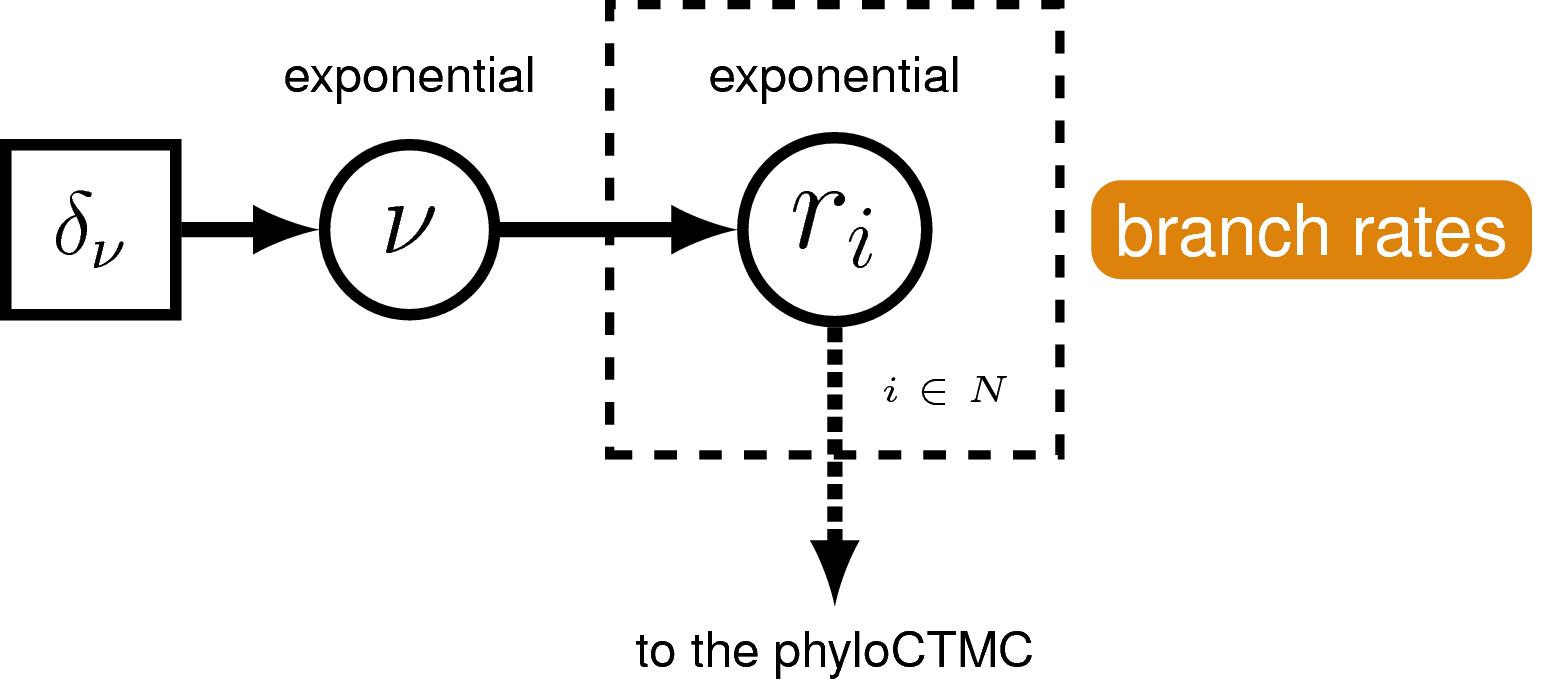

Rates of nucleotide sequence evolution can vary widely among lineages, and so models that account for this variation by relaxing the assumption of a strict molecular clock (Zuckerkandl and Pauling 1962) can allow for more accurate estimates of substitution rates and divergence times (Drummond et al. 2006). The simplest type of relaxed clock model assumes that lineage-specific substitution rates are independent or “uncorrelated”. One example of such an uncorrelated relaxed model is the uncorrelated exponential relaxed clock, in which the substitution rate for each lineage is assumed to be independent and identically distributed according to an exponential density (). This is Branch Rates Model for the Molecular Data () that we will use in this tutorial. Another possible uncorrelated relaxed clock model is the uncorrelated lognormal model, described in the Relaxed Clocks & Time Trees tutorial [also see Thorne and Kishino (2002)].

Morphological Character Evolution

For the vast majority of extinct species, fossil morphology is the primary source of phylogenetically informative characters. Therefore, an appropriate model of morphological character evolution is needed to reliably infer the positions of these species in a phylogenetic analysis. The Mk model (Lewis 2001) uses a generalized Jukes-Cantor matrix to allow for the incorporation of morphology into likelihood and Bayesian analyses. In its simplest form, this model assumes that characters change states symmetrically—that a given character is as likely to transition from a one state to another as it is to reverse. In this tutorial we will consider only binary morphological characters, i.e. characters that are observed in one of two states, 0 or 1. For example, the assumption of the single-rate Mk model applied to our binary character would mean that a change from a 0 state to a 1 state is as likely as a change from a 1 state to a 0 state. This assumption is equivalent to assuming that the stationary probability of being in a 1 state is equal to $1/2$.

In this tutorial, we will apply a single-rate Mk model as a prior on binary morphological character change. If you are interested extensions of the Mk model that relax the assumptions of symmetric state change, please see Discrete morphology - Tree Inference.

Because of the way morphological data are collected, we need to exercise caution in how we model the data. Traditionally, phylogenetic trees were built from morphological data using parsimony. Therefore, only parsimony informative characters were collected—that is, characters that are useful for discriminating between phylogenetic hypotheses under the maximum parsimony criterion. This means that many morphological datasets do not contain invariant characters or autapomorphies, as these are not parsimony informative. However, by excluding these slow-evolving characters, estimates of the branch lengths can be inflated (Felsenstein 1992; Lewis 2001). Therefore, it is important to use models that can condition on this data-acquisition bias. RevBayes has two ways of doing this: one is used for datasets in which only parsimony informative characters are observed; the other is for datasets in which parsimony informative characters and parsimony uninformative variable characters (such as autapomorphies) are observed.

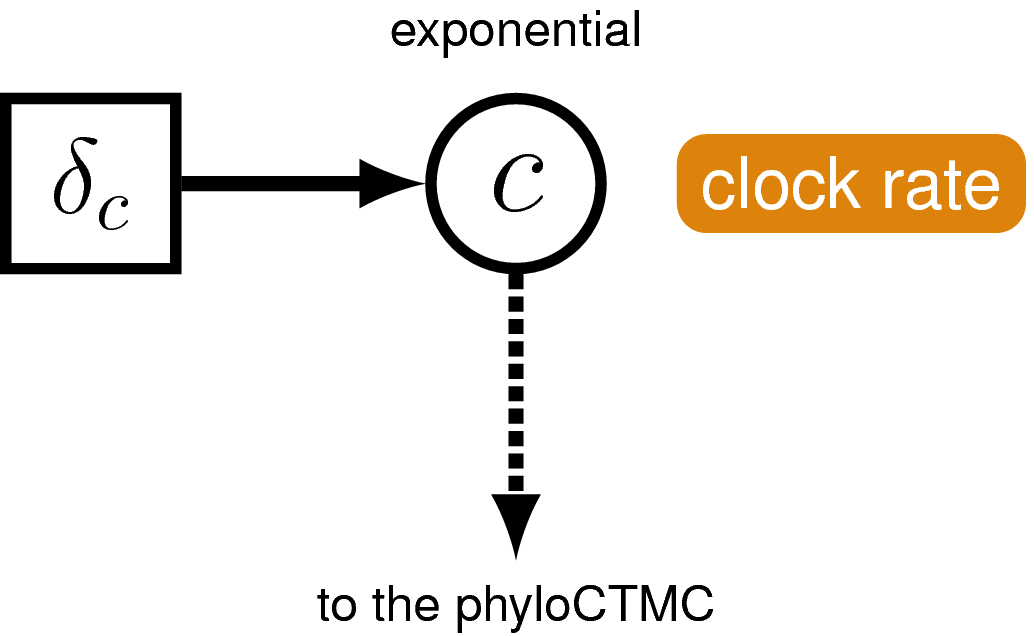

The Morphological Clock

Just like with the molecular data , our observations of discrete morphological characters are conditional on the rate of change along each branch in the tree. This model component defines the of the in the generalized graphical model shown in . The relaxed clock model we described for the molecular data in it allows the substitution rate to vary through time and among lineages. For the morphological data, we will instead use a “strict clock” model (Zuckerkandl and Pauling 1962), in which the rate of discrete character change is assumed to be constant throughout the tree. The strict clock is the simplest morphological branch rate model we can construct (graphical model shown in ).

Example: Estimating the Phylogeny and Divergence Times of Fossil and Extant Bears

In this exercise, we will combine different types of data from 22 species of extant and extinct bears to estimate a posterior distribution of calibrated time trees for this group. We have molecular sequence data for ten species, which represent all of the eight living bears and two extinct species sequenced from sub-fossil specimens (Arctodus simus, Ursus spelaeus). The sequence alignment provided is a 1,000 bp fragment of the cytochrome-b mitochondrial gene (Krause et al. 2008). The morphological character matrix unites 18 taxa (both fossil and extant) with 62 binary (states 0 or 1) characters (Abella et al. 2012). For the fossil species, occurrence times are obtained from the literature or fossil databases like the Paleobiology Database or from your own paleontological expertise. The 14 fossil species used in this analysis are listed in along with the age range for the species and relevant citation. Finally, there are two fossil species (Parictis montanus, Ursus abstrusus) for which we do not have morphological character data (or molecular data) and we must use prior information about their phylogenetic relationships to incorporate these taxa in our analysis. This information will be applied using clade constraints.

Data and Files

On your own computer or your remote machine, create a directory called

RB_CombinedEvidence_Tutorial(or any name you like).Then, navigate to the folder you created and make a new one called

data.Download the files listed below into the

datafolder. Click on the hyperlinked file names below (these files are also listed in the “Data files and scripts” box at the top of this page).

In the data folder, add the following files:

-

bears_taxa.tsv: a tab-separated table listing every bear species (both fossil and extant) and their occurrence age ranges. For extant taxa, the minimum age is 0.0 (i.e. the present). -

bears_cytb.nex: an alignment in NEXUS format of 1,000 bp of cytochrome b sequences for 10 bear species. This alignment includes 8 living bears and 2 extinct sub-fossil bears. -

bears_morphology.nex: a matrix of 62 discrete, binary (coded0or1) morphological characters for 18 species of fossil and extant bears.

Getting Started

Create a new directory called

scripts.

When you execute RevBayes in this exercise, you will do so within the

main directory you created (i.e., RB_CombinedEvidence_Tutorial).

Thus, if you are using a Unix-based operating system, we recommend that

you add the RevBayes binary to your path.

Creating Rev Files

For complex models and analyses, it is best to create Rev script files

that will contain all of the model parameters, moves, and functions. In

this exercise, you will work primarily in your text editor and

create a set of modular files that will be easily managed and

interchanged. You will write the following files from scratch and save

them in the scripts directory:

-

mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Rev: the master Rev file that loads the data, the separate model file and specifies the monitors and MCMC sampler. -

model_FBDP.Rev: specifies the model parameters and moves required for the fossilized birth-death prior on the tree topology, divergence times fossil occurrence times and diversification dynamics. -

model_UExp.Rev: specifies the components of the uncorrelated exponential model of lineage-specific substitution rate variation. -

model_GTRG.Rev: specifies the parameters and moves for the general time-reversible model of sequence evolution with gamma-distributed rates across sites (GTR+$\Gamma$). -

model_Morph.Rev: specifies the model describing discrete morphological character change (binary characters) under a strict morphological clock.

All of the files that you will create are also provided in the RevBayes tutorial at the top of the page to download. Please refer to these files to verify or troubleshoot your own scripts.

Start the Master Rev File and Import Data

In this section you will begin the master file that you will load into RevBayes when you’ve completed all of the components of the analysis.

Open your text editor and create the master Rev file called

mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Revin thescriptsdirectory.Enter the Rev code provided in this section in the new model file.

The file you will begin in this section will be the one you load into

RevBayes when you’ve completed all of the components of the analysis.

In this section you will begin the file and write the Rev commands for

loading in the taxon list and managing the data matrices. Then, starting

in section , you will move on to writing

module files for each of the model components. Once the model files are

complete, you will return to editing mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Rev and complete the

Rev script with the instructions given in section,

you will move on to writing the .

Load Taxon List

Begin the Rev script by loading in the list of taxon names from the

bears_taxa.tsv file using the readTaxonData function.

taxa <- readTaxonData("data/bears_taxa.tsv")

This function reads a tab-delimited file and creates a variable called

taxa that is a list of all of the taxon names relevant to this

analysis. This list includes all of the fossil and extant bear species

names in the first columns and a single age value in the second column.

The ages provided are either 0.0 for extant species or the average of

the age range for fossil species (see ).

Load Data Matrices

RevBayes uses the function readDiscreteCharacterData to load a

data matrix to the workspace from a formatted file. This function can be

used for both molecular sequences and discrete morphological characters.

Load the cytochrome-b sequences from file and assign the data matrix to

a variable called cytb.

cytb <- readDiscreteCharacterData("data/bears_cytb.nex")

Next, import the morphological character matrix and assign it to the

variable morpho.

morpho <- readDiscreteCharacterData("data/bears_morphology.nex")

Add Missing Taxa

In the descriptions of the files in section

, we mentioned that the two data matrices

have different numbers of taxa. Thus, we must add any taxa that are not

found in the molecular (cytb) partition

(i.e. are only found in the fossil data) to

that data matrix as missing data (with ? in place of all characters),

and do the same with the morphological data partition (morpho). In

order for all the taxa to appear on the same tree, they all need to be

part of the same dataset, as opposed to present in separate datasets.

This ensures that there is a unified taxon set that contains all of our

tips.

cytb.addMissingTaxa( taxa )

morpho.addMissingTaxa( taxa )

Create Helper Variables

Before we begin writing the Rev scripts for each of the model components, we need to instantiate a couple “helper variables” that will be used by downstream parts of our model specification files. These variables will be used in more than one of the module files so it’s best to initialize them in the master file.

Create a new constant node called n_taxa that is equal to the number

of species in our analysis (22).

n_taxa <- taxa.size()

Next, create a workspace variable called moves. This variable is a vector that will contain all of the MCMC moves used

to propose new states for every stochastic node in the model graph. Each

time a new stochastic node is created in the model, we can append the move to this vector.

moves = VectorMoves()

One important distinction here is that moves is part of the RevBayes

workspace and not the hierarchical model. Thus, we use the workspace

assignment operator = instead of the constant node assignment <-.

Save your current working version of

mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Revin thescriptsdirectory.

We will now move on to the next Rev file and will complete

mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Rev in section .

The Fossilized Birth-Death Process

Open your text editor and create the fossilized birth-death model file called

model_FBDP.Revin thescriptsdirectory.Enter the Rev code provided in this section in the new model file.

This file will define the models described in sections and above. If necessary, please review the graphical models depicted for the fossilized birth-death process () and the likelihood of the tip sampling process ().

Speciation and Extinction Rates

Two key parameters of the FBD process are the speciation rate (the rate at which lineages are added to the tree, denoted by $\lambda$ in ) and the extinction rate (the rate at which lineages are removed from the tree, $\mu$ in ). We’ll place exponential priors on both of these values. Each parameter is assumed to be drawn independently from a different exponential distribution with rates $\delta_{\lambda}$ and $\delta_{\mu}$ respectively (see ). Here, we will assume that $\delta_{\lambda} = \delta_{\mu} = 10$. Note that an exponential distribution with $\delta = 10$ has an expected value (mean) of $1/10$.

Create the exponentially distributed stochastic nodes for the

speciation_rate and extinction_rate using the ~ operator.

speciation_rate ~ dnExponential(10)

extinction_rate ~ dnExponential(10)

For every stochastic node we declare, we must also specify proposal algorithms (called moves) to sample the value of the parameter in proportion to its posterior probability. If a move is not specified for a stochastic node, then it will not be estimated, but fixed to its initial value.

The rate parameters for extinction and speciation are both positive,

real numbers (i.e. non-negative floating

point variables). For both of these nodes, we will use a scaling move

(mvScale), which proposes multiplicative changes to a parameter.

Many moves also require us to set a tuning value, called lambda for

mvScale, which determine the size of the proposed change. Here, we

will use three scale moves for each parameter with different values of

lambda. By using multiple moves for a single parameter, we will improve

the mixing of the Markov chain.

moves.append( mvScale(speciation_rate, lambda=0.01, weight=1) )

moves.append( mvScale(speciation_rate, lambda=0.1, weight=1) )

moves.append( mvScale(speciation_rate, lambda=1.0, weight=1) )

moves.append( mvScale(extinction_rate, lambda=0.01, weight=1) )

moves.append( mvScale(extinction_rate, lambda=0.1, weight=1) )

moves.append( mvScale(extinction_rate, lambda=1, weight=1) )

You will also notice that each move has a specified weight. This

option allows you to indicate how many times you would like a given move

to be performed at each MCMC cycle. The way that we will run our MCMC

for this tutorial will be to execute a schedule of moves at each step

in our chain instead of just one move per step, as is done in

MrBayes (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003) or BEAST

(Drummond et al. 2012; Bouckaert et al. 2014). Here, if we were to run our MCMC with

our current vector of 6 moves, then our move schedule would perform 6

moves at each cycle. Within a cycle, an individual move is chosen from

the move list in proportion to its weight. Therefore, with all six moves

assigned weight=1, each has an equal probability of being executed and

will be performed on average one time per MCMC cycle. For more

information on moves and how they are performed in RevBayes, please

refer to the Introduction to Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampling and Nucleotide substitution models tutorials.

In addition to the speciation ($\lambda$) and extinction ($\mu$) rates,

we may also be interested in inferring diversification ($\lambda - \mu$)

and turnover ($\mu/\lambda$). Since these parameters can be expressed as

a deterministic transformation of the speciation and extinction rates,

we can monitor (that is, track the values of these parameters, and print

them to a file) their values by creating two deterministic nodes using

the := operator.

diversification := speciation_rate - extinction_rate

turnover := extinction_rate/speciation_rate

Probability of Sampling Extant Taxa

All extant bears are represented in this dataset. Therefore, we will fix

the probability of sampling an extant lineage ($\rho$ in

) to 1. The parameter rho will be specified as a

constant node using the <- operator.

rho <- 1.0

Because $\rho$ is a constant node, we do not have to assign a move to this parameter.

The Fossil Sampling Rate

Since our data set includes serially sampled lineages, we must also

account for the rate of sampling back in time. This is the fossil

sampling (or recovery) rate ($\psi$ in ), which we

will instantiate as a stochastic node (named psi). As with the

speciation and extinction rates

(see ), we will use an

exponential prior on this parameter and use scale moves to sample values

from the posterior distribution.

psi ~ dnExponential(10)

moves.append( mvScale(psi, lambda=0.01, weight=1) )

moves.append( mvScale(psi, lambda=0.1, weight=1) )

moves.append( mvScale(psi, lambda=1, weight=1) )

The Origin Time

We will condition the FBD process on the origin time ($\phi$ in

) of bears, and we will specify a uniform

distribution on the origin age. For this parameter, we will use a

sliding window move (mvSlide). A sliding window samples a parameter

uniformly within an interval (defined by the half-width delta).

Sliding window moves can be tricky for small values, as the window may

overlap zero. However, for parameters such as the origin age, there is

little risk of this being an issue.

origin_time ~ dnUnif(37.2, 55.0)

moves.append( mvSlide(origin_time, delta=0.01, weight=5.0) )

moves.append( mvSlide(origin_time, delta=0.1, weight=5.0) )

moves.append( mvSlide(origin_time, delta=1, weight=5.0) )

Note that we specified a higher move weight for each of the proposals

operating on origin_time than we did for the three previous

stochastic nodes. This means that our move schedule will propose five

times as many updates to origin_time than it will to

speciation_rate, extinction_rate, or psi.

The FBD Distribution Object

All the parameters of the FBD process have now been specified. The next

step is to use these parameters to define the FBD tree prior

distribution, which we will call fbd_dist.

fbd_dist = dnBDSTP(r=0, origin=origin_time, lambda=speciation_rate, mu=extinction_rate, psi=psi, rho=rho, taxa=taxa)

Clade Constraints

Note that we created the distribution as a workspace variable using the

workspace assignment operator =. This is because we still need to

include a topology constraint in our final specification of the tree

prior. Specifically, we do not have any morphological or molecular data

for the fossil species Ursus abstrusus. Therefore, in order to use the

age of this fossil as an observation, we need to specify to which clade

it belongs. In this case, Ursus abstrusus belongs to the subfamily

Ursinae, so we define a clade for the total group Ursinae including

Ursus abstrusus.

clade_ursinae = clade("Melursus_ursinus", "Ursus_arctos", "Ursus_maritimus",

"Helarctos_malayanus", "Ursus_americanus", "Ursus_thibetanus",

"Ursus_abstrusus", "Ursus_spelaeus")

Then we can specify the final constrained tree prior distribution by

creating a vector of constraints, and providing it along with the

workspace FBD distribution to the constrained topology distribution.

Here we use the stochastic assignment operator ~ to create a

stochastic node for our constrained FBD-tree variable (called

fbd_tree).

constraints = v(clade_ursinae)

fbd_tree ~ dnConstrainedTopology(fbd_dist, constraints=constraints)

It is important to recognize that we do not know if Ursus abstrusus is a crown or stem Ursinae. Because of this, we defined this clade constraint so that it constrained the total group Ursinae and this uncertainty is taken into account. As a result, our MCMC will marginalize over both stem and crown positions of U. abstrusus and sample the phylogeny in proportion to its posterior probability, conditional on our model and data.

Additionally, we do not have morphological data for the fossil species Parictis montanus. However, we will not create a clade constraint for this taxon because it is a very old, stem-fossil bear. Thus, the MCMC may propose to place this taxon anywhere in the tree (except within the clade constraint we made above). This allows us to account for the maximum amount of uncertainty in the placement of P. montanus.

Moves on the Tree Topology and Node Ages

Next, in order to sample from the posterior distribution of trees, we

need to specify moves that propose changes to the topology (mvFNPR)

and node times (mvNodeTimeSlideUniform). Included with these moves is

a proposal that will collapse or expand a fossil branch

(mvCollapseExpandFossilBranch). This will change a fossil that is a

sampled ancestor (see and

) so that it is on its own branch and vice

versa. In addition, when conditioning on the origin time, we also need

to explicitly sample the root age (mvRootTimeSlideUniform).

moves.append( mvFNPR(fbd_tree, weight=15.0) )

moves.append( mvCollapseExpandFossilBranch(fbd_tree, origin_time, weight=6.0) )

moves.append( mvNodeTimeSlideUniform(fbd_tree, weight=40.0) )

moves.append( mvRootTimeSlideUniform(fbd_tree, origin_time, weight=5.0) )

Sampling Fossil Occurrence Ages

Next, we need to account for uncertainty in the age estimates of our

fossils using the observed minimum and maximum stratigraphic ages.

To do this, we get all the fossils from the tree and use a for loop to iterate over them.

For each fossil observation, we create a

uniform random variable representing the likelihood. Remember, we can

represent the fossil likelihood using any uniform distribution that is

non-zero when the likelihood is equal to one

(see ).

For example, if $t_i$ is the inferred fossil age and $(a_i,b_i)$ is the observed stratigraphic interval, we know the likelihood is equal to one when $a_i < t_i < b_i$, or equivalently $t_i - b_i < 0 < t_i - a_i$. So let’s represent the likelihood using a uniform random variable uniformly distributed in $(t_i - b_i, t_i - a_i)$ and clamped at zero.

fossils = fbd_tree.getFossils()

for(i in 1:fossils.size())

{

t[i] := tmrca(fbd_tree, clade(fossils[i]))

a_i = fossils[i].getMinAge()

b_i = fossils[i].getMaxAge()

F[i] ~ dnUniform(t[i] - b_i, t[i] - a_i)

F[i].clamp( 0 )

}

Finally, we add a move that samples the ages of the fossil nodes on the tree.

moves.append( mvFossilTimeSlideUniform(fbd_tree, origin_time, weight=5.0) )

Monitoring Parameters of Interest using Deterministic Nodes

There are additional parameters that may be of particular interest to us

that are not directly inferred as part of this graphical model. As with

the diversification and turnover nodes specified in

, we can create

deterministic nodes to sample the posterior distributions of these

parameters. Create a deterministic node called num_samp_anc that

will compute the number of sampled ancestors in our fbd_tree.

num_samp_anc := fbd_tree.numSampledAncestors();

We are also interested in the age of the most-recent-common ancestor

(MRCA) of all living bears. To monitor the age of this node in our MCMC

sample, we must use the clade function to identify the node.

Importantly, since we did not include this clade in our constraints that

defined fbd_tree, this clade will not be constrained to be

monophyletic. Once this clade is defined we can instantiate a

deterministic node called age_extant with the tmrca function that

will record the age of the MRCA of all living bears.

clade_extant = clade("Ailuropoda_melanoleuca","Tremarctos_ornatus","Melursus_ursinus",

"Ursus_arctos","Ursus_maritimus","Helarctos_malayanus",

"Ursus_americanus","Ursus_thibetanus")

age_extant := tmrca(fbd_tree, clade_extant)

In the same way we monitored the MRCA of the extant bears, we can also monitor the age of a fossil taxon that we may be interested in recording. We will monitor the marginal distribution of the age of Kretzoiarctos beatrix, which is between 11.2–11.8 My.

age_Kretzoiarctos_beatrix := tmrca(fbd_tree, clade("Kretzoiarctos_beatrix"))

Finally, we will monitor the tree after removing taxa for which we did not have any molecular or morphological data. The phylogenetic placement of these taxa is based only on their occurrence times and any clade constraints we applied (see ). Because no data are available to resolve their relationships to other lineages, we will treat their placement as nuisance parameters and remove them from the output.

We will remove two fossil taxa, Parictis montanus and Ursus

abstrusus, from every tree in the trace file before summarizing the

samples. Use the fnPruneTree function to create a deterministic tree

variable pruned_tree from which these taxa have been pruned. We will

monitor this tree instead of fbd_tree.

pruned_tree := fnPruneTree(fbd_tree, prune=v(taxa[17],taxa[20]))

You have completed the FBD model file. Save

model_FBDP.Revin thescriptsdirectory.

We will now move on to the next model file.

The Uncorrelated Exponential Relaxed Clock Model

We will now define the molecular relaxed clock model.

Open your text editor and create the lineage-specific branch-rate model file called

model_UExp.Revin thescriptsdirectory.Enter the Rev code provided in this section in the new model file.

For our hierarchical, uncorrelated exponential relaxed clock model (described in section and shown in ), we first define the mean branch rate as an exponential random variable. Then, we specify scale proposal moves on the mean rate parameter.

branch_rates_mean ~ dnExponential(10.0)

moves.append( mvScale(branch_rates_mean, lambda=0.01, weight=1.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(branch_rates_mean, lambda=0.1, weight=1.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(branch_rates_mean, lambda=1.0, weight=1.0) )

Before creating a rate parameter for each branch, we need to get the number of branches in the tree. For rooted trees with $n$ taxa, the number of branches is $2n-2$.

n_branches <- 2 * n_taxa - 2

Then, use a for loop to define a rate for each branch. The branch rates are independent and identically exponentially distributed with mean equal to the mean branch rate parameter we specified above. For each rate parameter we also create scale proposal moves.

for(i in 1:n_branches){

branch_rates[i] ~ dnExp(1/branch_rates_mean)

moves.append( mvScale(branch_rates[i], lambda=1.0, weight=1.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(branch_rates[i], lambda=0.1, weight=1.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(branch_rates[i], lambda=0.01, weight=1.0) )

}

Lastly, we use a vector scale move to propose changes to all branch rates simultaneously. This way we can sample the total branch rate independently of each individual rate, which can improve mixing.

moves.append( mvVectorScale(branch_rates, lambda=0.01, weight=4.0) )

moves.append( mvVectorScale(branch_rates, lambda=0.1, weight=4.0) )

moves.append( mvVectorScale(branch_rates, lambda=1.0, weight=4.0) )

You have completed the molecular relaxed clock model file. Save model_UExp.Rev in

the scripts directory.

The General Time-Reversible + Gamma Model of Nucleotide Sequence Evolution

In this section we will define our nucleotide sequence evolution model.

Open your text editor and create the molecular substitution model file called

model_GTRG.Revin thescriptsdirectory.Enter the Rev code provided in this section in the new model file.

For our nucleotide sequence evolution model, we need to define a general time-reversible (GTR) instantaneous-rate matrix (i.e. $Q$-matrix). A nucleotide GTR matrix is defined by a set of 4 stationary frequencies, and 6 exchangeability rates. We create stochastic nodes for these variables, each drawn from a uniform Dirichlet prior distribution.

sf_hp <- v(1,1,1,1)

sf ~ dnDirichlet(sf_hp)

er_hp <- v(1,1,1,1,1,1)

er ~ dnDirichlet(er_hp)

We need special moves to propose changes to a Dirichlet random variable,

also known as a simplex (a vector constrained sum to one). Here, we use

a mvSimplexElementScale move, which scales a single element of a

simplex and then renormalizes the vector to sum to one. The tuning

parameter alpha specifies how conservative the proposal should be,

with larger values of alpha leading to proposals closer to the current

value.

moves.append( mvSimplexElementScale(er, alpha=10.0, weight=5.0) )

moves.append( mvSimplexElementScale(sf, alpha=10.0, weight=5.0) )

Then we can define a deterministic node for our GTR $Q$-matrix using the

special GTR matrix function (fnGTR).

Q_cytb := fnGTR(er,sf)

Next, in order to model gamma-distributed rates across, we create an exponential parameter $\alpha$ for the shape of the gamma distribution, along with scale proposals.

alpha_cytb ~ dnExponential( 1.0 )

moves.append( mvScale(alpha_cytb, lambda=0.01, weight=1.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(alpha_cytb, lambda=0.1, weight=1.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(alpha_cytb, lambda=1, weight=1.0) )

Then we create a Gamma$(\alpha,\alpha)$ distribution, discretized into 4

rate categories using the fnDiscretizeGamma function. Here,

rates_cytb is a deterministic vector of rates computed as the mean of

each category.

rates_cytb := fnDiscretizeGamma( alpha_cytb, alpha_cytb, 4 )

Finally, we can create the phylogenetic continuous time Markov chain

(PhyloCTMC) distribution for our sequence data, including the

gamma-distributed site rate categories, as well as the branch rates

defined as part of our exponential relaxed clock. We set the value of

this distribution equal to our observed data and identify it as a static

part of the likelihood using the clamp method.

phySeq ~ dnPhyloCTMC(tree=fbd_tree, Q=Q_cytb, siteRates=rates_cytb, branchRates=branch_rates, type="DNA")

phySeq.clamp(cytb)

You have completed the GTR model file. Save

model_GTRG.Revin thescriptsdirectory.

We will now move on to the next model file.

Modeling the Evolution of Binary Morphological Characters

In this section we will define the model of morphological character evolution.

Open your text editor and create the morphological character model file called

model_Morph.Revin thescriptsdirectory.

As stated in the introduction () we will use Mk to model our data. Because the Mk model is a generalization of the Jukes-Cantor model, we will initialize our Q matrix from a Jukes-Cantor matrix.

Q_morpho := fnJC(2)

As in the molecular data partition, we will allow gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity among sites.

alpha_morpho ~ dnExponential( 1.0 )

rates_morpho := fnDiscretizeGamma( alpha_morpho, alpha_morpho, 4 )

moves.append( mvScale(alpha_morpho, lambda=0.01, weight=5.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(alpha_morpho, lambda=0.1, weight=3.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(alpha_morpho, lambda=1, weight=1.0) )

The phylogenetic model also assumes that each branch has a rate of morphological character change. For simplicity, we will assume a strict exponential clock—meaning that every branch has the same rate drawn from an exponential distribution (see ).

clock_morpho ~ dnExponential(1.0)

moves.append( mvScale(clock_morpho, lambda=0.01, weight=4.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(clock_morpho, lambda=0.1, weight=4.0) )

moves.append( mvScale(clock_morpho, lambda=1, weight=4.0) )

As in our molecular data partition, we now combine our data and our model in the phylogenetic CTMC distribution. There are some unique aspects to doing this for morphology.

You will notice that we have an option called coding. This option

allows us to condition on biases in the way the morphological data were

collected (ascertainment bias). The option coding=variable specifies

that we should correct for coding only variable characters (discussed in

).

phyMorpho ~ dnPhyloCTMC(tree=fbd_tree, siteRates=rates_morpho, branchRates=clock_morpho, Q=Q_morpho, type="Standard", coding="variable")

phyMorpho.clamp(morpho)

You have completed the morphology model file. Save model_Morph.Rev in

the scripts directory.

We will now move on to the next model file.

Complete Master Rev File

Return to the master Rev file you created in section called

mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Revin thescriptsdirectory.Enter the Rev code provided in this section in this file.

Source Model Scripts

RevBayes uses the source function to load commands from Rev

files into the workspace. Use this function to load in the model scripts

we have written in the text editor and saved in the scripts directory.

source("scripts/model_FBDP.Rev") # FBD tree prior

source("scripts/model_UExp.Rev") # UExp relaxed clock

source("scripts/model_GTRG.Rev") # Molecular substitution model (GTR+G)

source("scripts/model_Morph.Rev") # Morphological character change model

Create Model Object

We can now create our workspace model variable with our fully specified

model DAG. We will do this with the model function and provide a

single node in the graph (sf).

mymodel = model(sf)

The object mymodel is a wrapper around the entire model graph and

allows us to pass the model to various functions that are specific to

our MCMC analysis.

Specify Monitors and Output Filenames

The next important step for our master Rev file is to specify the

monitors and output file names. For this, we create a vector called

monitors that will each sample and record or output our MCMC.

monitors = VectorMonitors()

The first monitor we will create will monitor every named random

variable in our model graph. This will include every stochastic and

deterministic node using the mnModel monitor. The only parameter that

is not included in the mnModel is the tree topology. Therefore, the

parameters in the file written by this monitor are all numerical

parameters written to a tab-separated text file that can be opened by

accessory programs for evaluating such parameters. We will also name the

output file for this monitor and indicate that we wish to sample our

MCMC every 10 cycles.

monitors.append( mnModel(filename="output/bears.log", printgen=10) )

The mnFile monitor writes any parameter we specify to file. Thus, if

we only cared about the speciation rate and nothing else (this is not a

typical or recommended attitude for an analysis this complex) we

wouldn’t use the mnModel monitor above and just use the mnFile

monitor to write a smaller and simpler output file. Since the tree

topology is not included in the mnModel monitor (because it is not

numerical), we will use mnFile to write the tree to file by specifying

our pruned_tree variable in the arguments. Remember, we are

monitoring the tree with nuisance taxa pruned out (see

).

monitors.append( mnFile(filename="output/bears.trees", printgen=10, pruned_tree) )

The last monitor we will add to our analysis will print information to

the screen. Like with mnFile we must tell mnScreen which parameters

we’d like to see updated on the screen. We will choose the age of the

MCRCA of living bears (age_extant), the number of sampled ancestors

(num_samp_anc), and the origin time (origin_time).

monitors.append( mnScreen(printgen=10, age_extant, num_samp_anc, origin_time) )

Set-Up the MCMC

Once we have set up our model, moves, and monitors, we can now create

the workspace variable that defines our MCMC run. We do this using the

mcmc function that simply takes the three main analysis components

as arguments.

mymcmc = mcmc(mymodel, monitors, moves)

The MCMC object that we named mymcmc has a member method called

run. This will execute our analysis and we will set the chain

length to 10000 cycles using the generations option.

mymcmc.run(generations=10000)

Once our Markov chain has terminated, we will want RevBayes to close.

Tell the program to quit using the q() function.

q()

You made it! Save all of your files.

Execute the MCMC Analysis

With all the parameters specified and all analysis components in place, you are now ready to run your analysis. The Rev scripts you just created will all be used by RevBayes and loaded in the appropriate order.

Begin by running the RevBayes executable. In Unix systems, type the following in your terminal (if the RevBayes binary is in your path):

Provided that you started RevBayes from the correct directory, you can then use the

source function to feed RevBayes your master script file

(mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Rev).

source("scripts/mcmc_CEFBDP_Specimens.Rev")

This will execute the analysis and you should see the various parameters you included when you created mnScreen printed to the screen every 10 generations.

When the analysis is complete, RevBayes will quit and you will have a

new directory called output that will contain all of the files you

specified with the monitors (see ).

Evaluate and Summarize Your Results

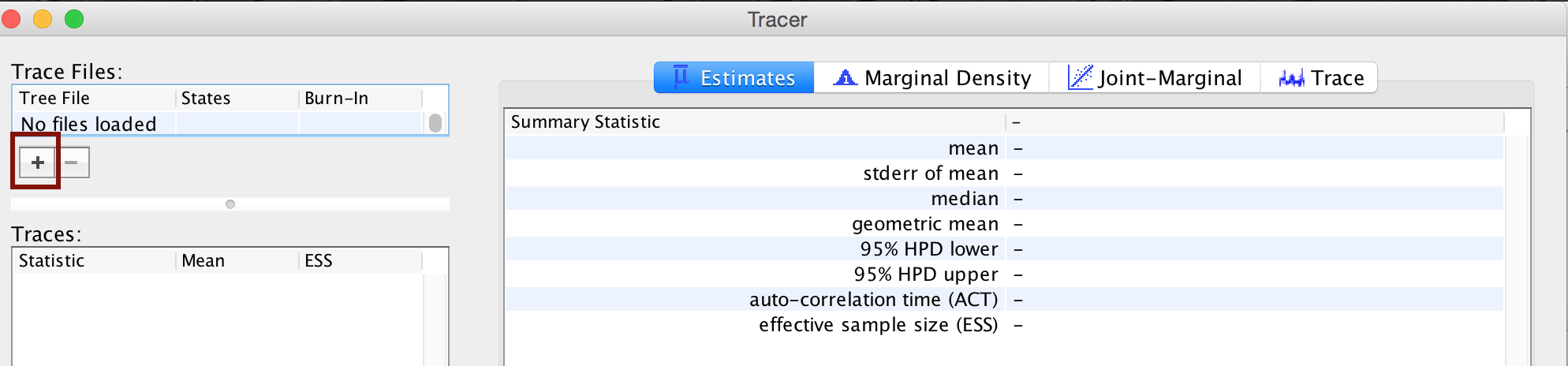

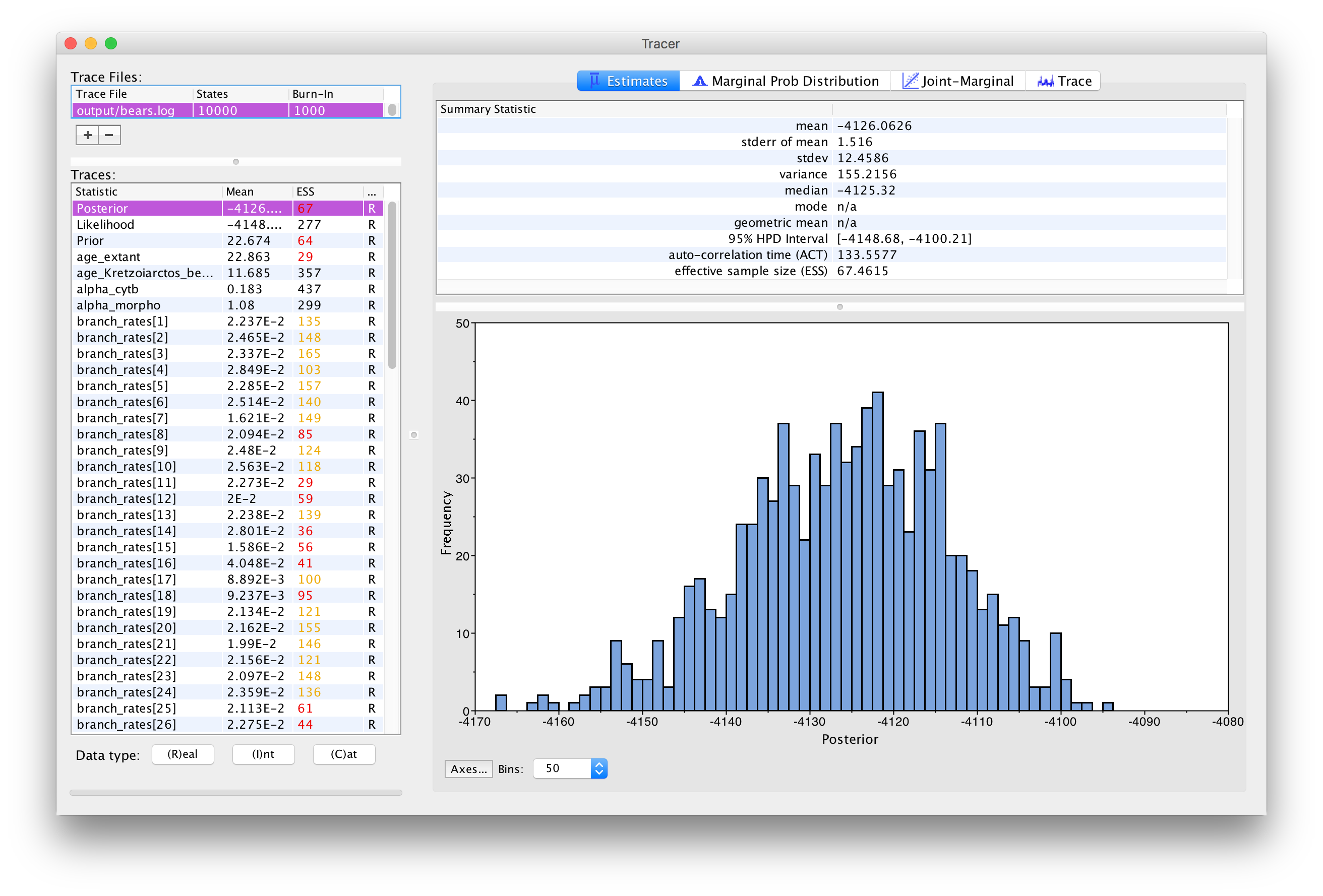

In this section, we will evaluate the mixing and convergence of our MCMC simulation using the program Tracer. We can also summarize the marginal distributions for particular parameters we’re interested in. Tracer (Rambaut and Drummond 2011) is a tool for visualizing parameters sampled by MCMC. This program is limited to numerical parameters, however, and cannot be used to summarize or analyze MCMC samples of the tree topology (this will be discussed further in ).

Open Tracer and import the bears.log file in the

File > Import New Trace Files. Or click the button on the

left-hand side of the screen to add your log file (see ).

Immediately upon loading your file (see ), you will see the list of Trace Files on the left-hand side (you can load multiple files). The bottom left section, called Traces, provides a list of every parameter in the log file, along with the mean and the effective sample size (ESS) for the posterior sample of that parameter. The ESS statistic provides a measure of the number of independent draws in our sample for a given parameter. This quantity will typically be much smaller than the number of generations of the chain. In Tracer, poor to fair values for the ESS will be colored red and yellow. You will likely see a lot of red and yellow numbers because the MCMC runs in this exercise are too short to effectively sample the posterior distributions of most parameters. For most MCMC analyses, it is recommended to run the chain for much longer so that you get an adequate sample from the target distribution.

The inspection window for your selected parameter is the

Estimates window, which shows a histogram and summary

statistics of the values sampled by the Markov chain.

shows the marginal distribution of the

Posterior statistic for the bears.log file for an analysis run for 10,000 generations.

Look through the various parameters and statistics in the list of Traces.

⇨ Are there any parameters that have really low ESS? Why do you think that might be?

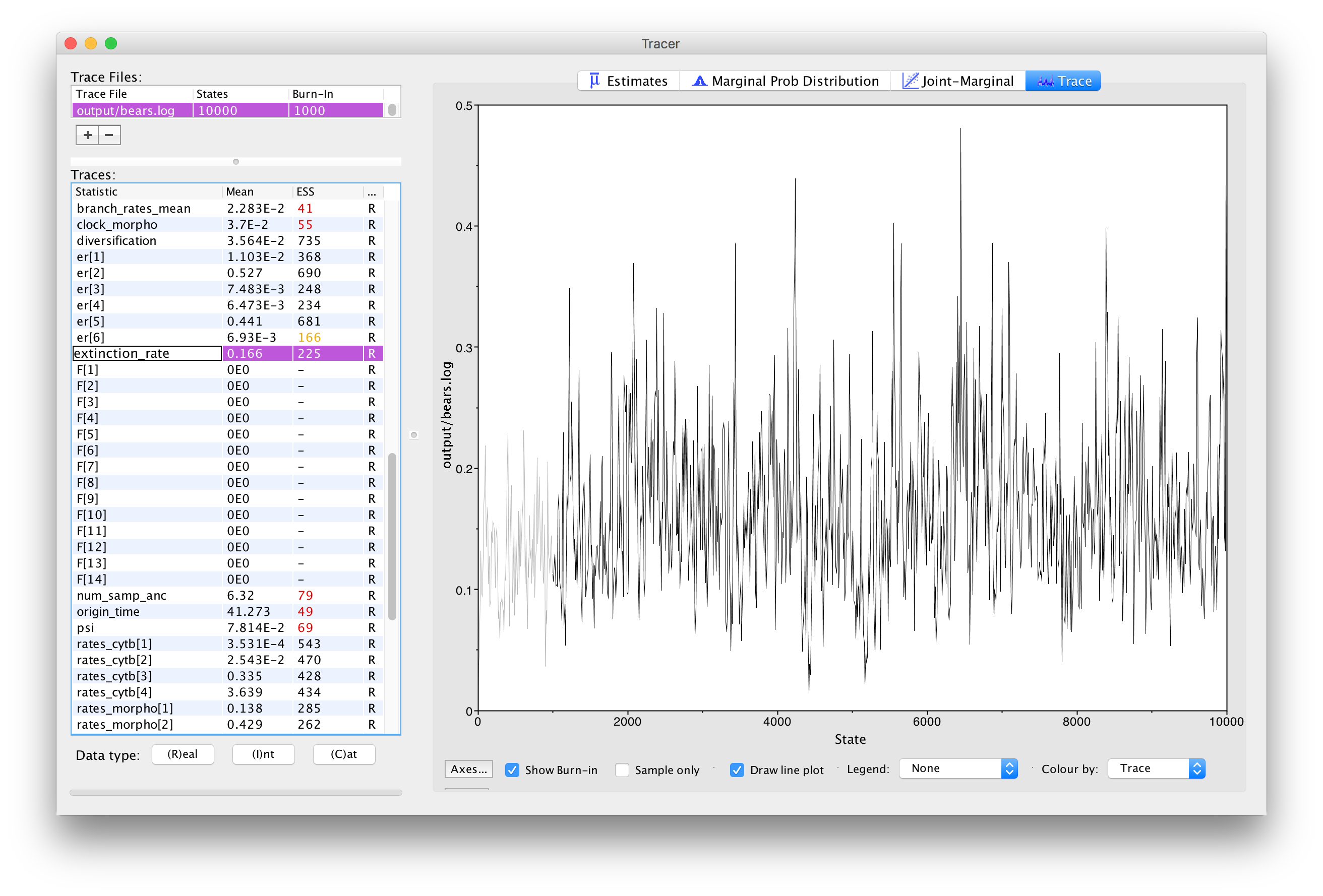

Next, we can click over to the Trace window. This window shows us the samples for a given parameter at each iteration of the MCMC. The left side of the chain has a shaded portion that has been excluded as “burn-in”. Samples taken near the beginning of chain are often discarded or “burned” because the MCMC may not immediately begin sampling from the target posterior distribution, particularly if the starting condition of the chain is far from the region of highest posterior density. shows the trace for the extinction rate.

The Trace window allows us to evaluate how well our chain is sampling the target distribution. For a fairly short analysis, the output in shows reasonable mixing—there is no consistent pattern or trend in the samples, nor are there long intervals where the statistic does not change. The presence of a trend or large leaps in a parameter value might indicate that your MCMC is not mixing well. You can read more about MCMC tuning and improving mixing in the tutorials Introduction to Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampling.

Look through the traces for your parameters.

⇨ Are there any parameters in your log files that show trends or large leaps?

⇨ What steps might you take to solve these issues?

In Tracer you can view the marginal probability distributions of your parameters in the Marginal Prob Distribution window. Using this tool, you can compare the distributions of several different parameters (by selecting them both).

Go to the

diversificationparameter in the Marginal Prob Distribution window.⇨ What is the mean value estimated for the net diversification rate ($d$)?

⇨ What does the marginal distribution tell you about the net diversification? (Hint: $d = \lambda - \mu$)

While specifying the model, remember that we created several deterministic nodes that represent parameters that we would like to estimate, including the net diversification rate. Tracer allows us to view the summaries of these parameters since they appear in our log files.

Go to the

age_extantparameter in the Estimates window.⇨ What is the mean and 95% highest posterior density of the age of the MRCA for all living bears?

Since you have evaluated several of the parameters by viewing the trace files and the ESS values, you may be aware that the MCMC analysis you conducted for this tutorial did not sufficiently sample the joint posterior distribution of phylogenetic parameters. More explicitly, your run has not converged. It is not advisable to base your conclusions on such a run and it will be critical to perform multiple, independent runs for many more MCMC cycles. For further discussion of recommended MCMC practices in RevBayes, please see the Introduction to Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampling tutorials.

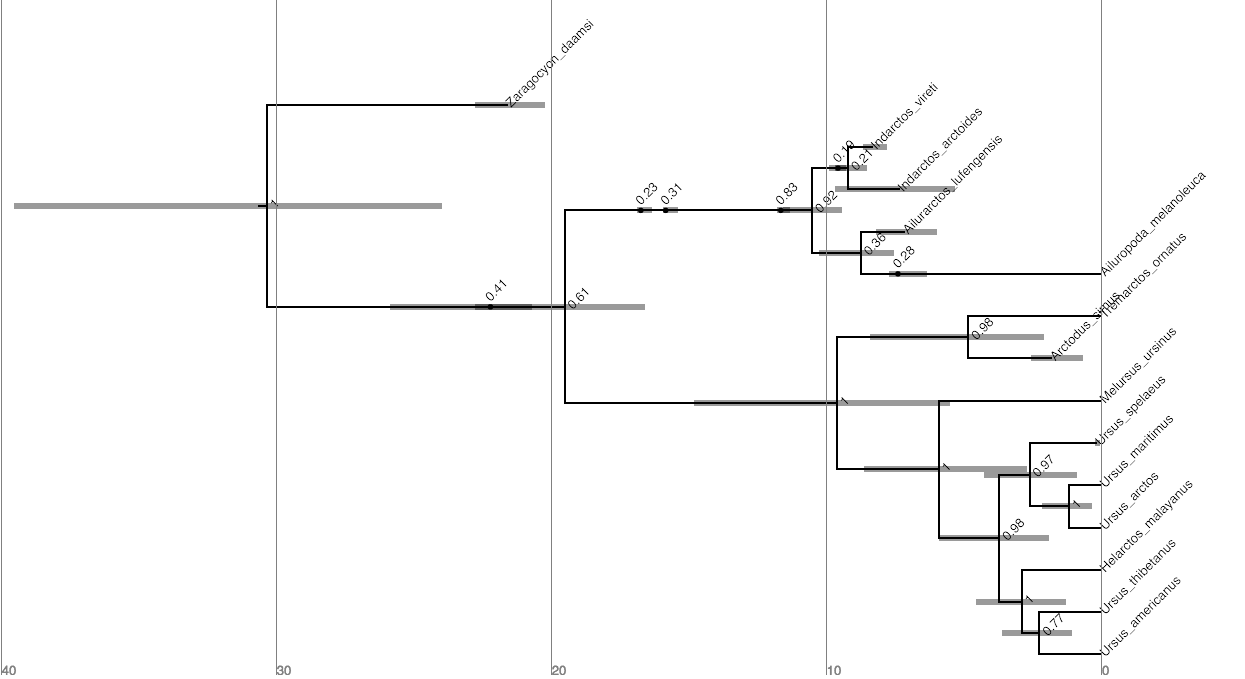

Summarize Tree

In addition to evaluating the performance and sampling of an MCMC run using numerical parameters, it is also important to inspect the sampled topology and tree parameters. This is a difficult endeavor, however. One tool for evaluating convergence and mixing of the tree samples is RWTY (Warren et al. 2016). In this tutorial, we will only summarize the sampled trees, but we encourage you to consider approaches for assessing the performance of the MCMC with respect to the tree topology.

Ultimately, we are interested in summarizing the sampled trees and branch times given that our MCMC has sampled all of the important parameters in proportion to their posterior probabilities. RevBayes includes some functions for summarizing the tree topology and other tree parameters.

We will complete this part of the tutorial using RevBayes interactively.

Begin by running the RevBayes executable. You should do this from within the tutorial directory.

Read in the MCMC sample of trees from file.

trace = readTreeTrace("output/bears.trees")

By default, a burn-in of 25% is used when creating the tree trace (250

trees in our case). You can specify a different burn-in fraction, say

50%, by typing the command trace.setBurnin(500).

Now we will use the mccTree function to return a maximum clade

credibility (MCC) tree. The MCC tree is the tree with the maximum

product of the posterior clade probabilities. When considering trees

with sampled ancestors, we refer to the maximum sampled ancestor clade

credibility (MSACC) tree (Gavryushkina et al. 2017).

mccTree(trace, file="output/bears.mcc.tre" )

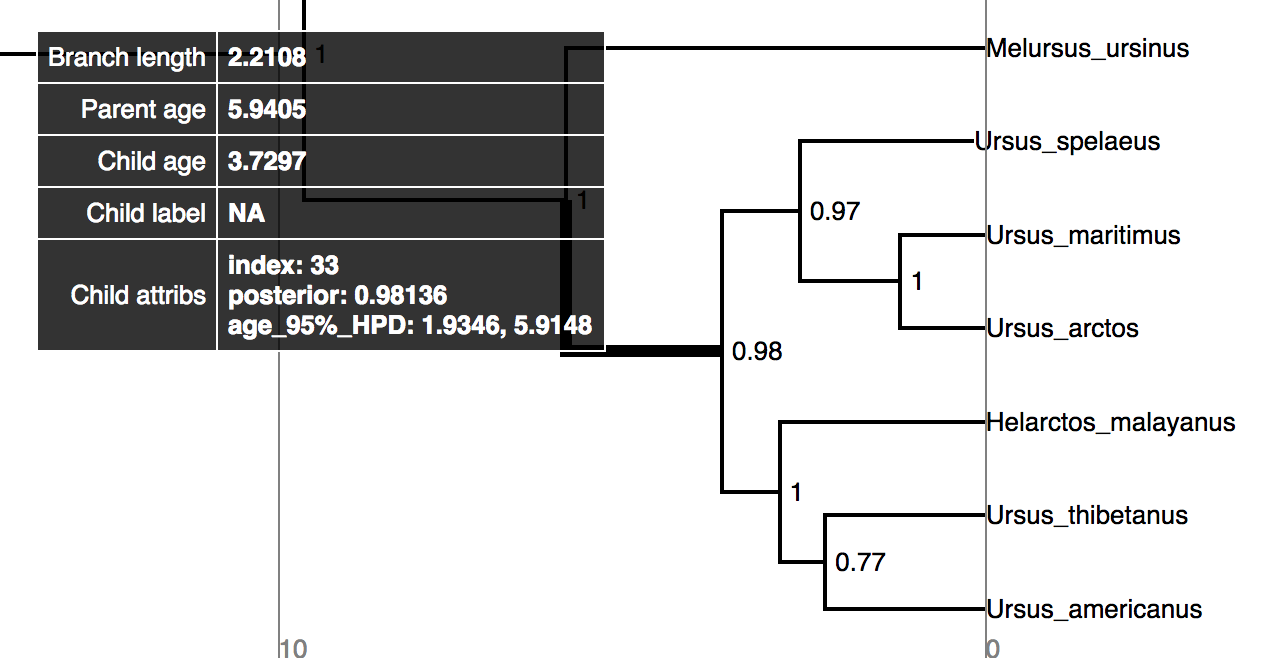

When there are sampled ancestors present in the tree, visualizing the tree can be fairly difficult in traditional tree viewers. We will make use of a browser-based tree viewer called IcyTree, created by Tim Vaughan. IcyTree has many unique options for visualizing phylogenetic trees and can produce publication-quality vector image files (i.e. SVG). Additionally, it correctly represents sampled ancestors on the tree as nodes, each with only one descendant ().

Navigate to https://icytree.org and open the file

output/bears.mcc.tre in IcyTree.

Try to replicate the tree in (Hint: Style > Mark Singletons)

⇨ Why might a node with a sampled ancestor be referred to as a singleton?

⇨ How can you see the names of the fossils that are putative sampled ancestors?

Try mousing over different branches (see ). What are the fields telling you?

⇨ What is the posterior probability that Zaragocyon daamsi is a sampled ancestor?

Another newly available web-based tree viewer is Phylogeny.IO (Jovanovic and Mikheyev 2016). Try this site for a different way to view the tree.

- Abella J., Montoya P., Morales J. 2011. Una nueva especie de Agriarctos (Ailuropodinae, Ursidae, Carnivora) en la localidad de Nombrevilla 2 (Zaragoza, España). Estudios Geológicos. 67:187–191.

- Abella J., Alba D.M., Robles J.M., Valenciano A., Rotgers C., Carmona R., Montoya P., Morales J. 2012. Kretzoiarctos gen. nov., the Oldest Member of the Giant Panda Clade. PLoS One. 17:e48985.

- Andrews P., Tobien H. 1977. New Miocene locality in Turkey with evidence on the origin of Ramapithecus and Sivapithecus. Nature. 268:699.

- Baryshnikov G.F. 2002. Late Miocene Indarctos punjabiensis atticus (Carnivora, Ursidae) in Ukraine with survey of Indarctos records from the former USSR. Russian J. Theriol. 1:83–89.

- Bjork P.R. 1970. The Carnivora of the Hagerman local fauna (late Pliocene) of Southwestern Idaho. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 60:3–54.

- Bouckaert R., Heled J., Kühnert D., Vaughan T., Wu C.-H., Xie D., Suchard M.A., Rambaut A., Drummond A.J. 2014. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Computational Biology. 10:e1003537. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537

- Churcher C.S., Morgan A.V., Carter L.D. 1993. Arctodus simus from the Alaskan Arctic slope. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30:1007–1013.

- Clark J., Guensburg T.E. 1972. Arctoid Genetic Characters as Related to the Genus Parictis. Chicago, Ill.: Field Museum of Natural History.

- Drummond A.J., Suchard M.A., Xie D., Rambaut A. 2012. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29:1969–1973. 10.1093/molbev/mss075

- Drummond A.J., Ho S.Y.W., Phillips M.J., Rambaut A. 2006. Relaxed Phylogenetics and Dating with Confidence. PLoS Biology. 4:e88. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088

- Felsenstein J. 1992. Phylogenies from Restriction Sites: A Maximum-Likelihood Approach. Evolution. 46:159–173. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1992.tb01991.x

- Foote M. 1996. On the probability of ancestors in the fossil record. Paleobiology. 22:141–151. 10.1017/S0094837300016146

- Gavryushkina A., Heath T.A., Ksepka D.T., Stadler T., Welch D., Drummond A.J. 2017. Bayesian Total-Evidence Dating Reveals the Recent Crown Radiation of Penguins. Systematic Biology. 66:57–73. 10.1093/sysbio/syw060

- Geraads D., Kaya T., Mayda S., others. 2005. Late Miocene large mammals from Yulafli, Thrace region, Turkey, and their biogeographic implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 50:523–544.

- Ginsburg L., Morales J. 1995. Zaragocyon daamsi n. gen. sp. nov., Ursidae primitif du Miocène inférieur d’Espagne. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences. Série 2. Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes. 321:811–815.

- Ginsburg L., Morales J. 1998. Les Hemicyoninae (Ursidae, Carnivora, Mammalia) et les formes apparentées du Miocène inférieur et moyen d’Europe occidentale. Annales de Paléontologie. 84:71–123.

- Heath T.A., Huelsenbeck J.P., Stadler T. 2014. The fossilized birth-death process for coherent calibration of divergence-time estimates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111:E2957–E2966. 10.1073/pnas.1319091111

- Heizmann E., Ginsburg L., Bulot C. 1980. Prosansanosmilus peregrinus, ein neuer machairodontider Felidae aus dem Miozän Deutschlands und Frankreichs. Stuttgarter Beitr. Naturk. B. 58:1–27.

- Höhna S., Heath T.A., Boussau B., Landis M.J., Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. 2014. Probabilistic Graphical Model Representation in Phylogenetics. Systematic Biology. 63:753–771. 10.1093/sysbio/syu039

- Höhna S., Landis M.J., Heath T.A. 2017. Phylogenetic Inference using RevBayes. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 10.1002/cpbi.22

- Jin C., Ciochon R.L., Dong W., Hunt R.M., Liu J., Jaeger M., Zhu Q. 2007. The first skull of the earliest giant panda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104:10932–10937. 10.1073/pnas.0704198104

- Jovanovic N., Mikheyev A.S. 2016. Interactive web-based visualization of phylogenetic trees using Phylogeny. IO. PeerJ Preprints. 4:e2579v1.

- Krause J., Unger T., Noçon A., Malaspinas A.-S., Kolokotronis S.-O., Stiller M., Soibelzon L., Spriggs H., Dear P.H., Briggs A.W., others. 2008. Mitochondrial genomes reveal an explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8:220.

- Lewis P.O. 2001. A Likelihood Approach to Estimating Phylogeny from Discrete Morphological Character Data. Systematic Biology. 50:913–925. 10.1080/106351501753462876

- Loreille O., Orlando L., Patou-Mathis M., Philippe M., Taberlet P., Hänni C. 2001. Ancient DNA analysis reveals divergence of the cave bear, Ursus spelaeus, and brown bear, Ursus arctos, lineages. Current Biology. 11:200–203.

- Montoya P., Alcalá L., Morales J. 2001. Indarctos (Ursidae, Mammalia) from the Spanish Turolian (Upper Miocene). Scripta Geologica. 122:123–151.

- Rambaut A., Drummond A.J. 2011. Tracer v1.5. . http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 19:1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180

- Ronquist F., Klopfstein S., Vilhelmsen L., Schulmeister S., Murray D.L., Rasnitsyn A.P. 2012. A total-evidence approach to dating with fossils, applied to the early radiation of the Hymenoptera. Systematic Biology. 61:973–999.

- Stadler T. 2010. Sampling-through-time in birth-death trees. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 267:396–404. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.09.010

- Stadler T., Gavryushkina A., Warnock R.C.M., Drummond A.J., Heath T.A. 2018. The fossilized birth-death model for the analysis of stratigraphic range data under different speciation modes. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 447:41–55.

- Thorne J.L., Kishino H. 2002. Divergence time and evolutionary rate estimation with multilocus data. Systematic Biology. 51:689–702. 10.1080/10635150290102456

- Warren D.L., Geneva A., Swofford D.L., Lanfear R. 2016. rwty: R We There Yet. A package for visualizing MCMC convergence in phylogenetics.

- Zhang C., Stadler T., Klopfstein S., Heath T.A., Ronquist F. 2016. Total-Evidence Dating under the Fossilized Birth-Death Process. Systematic Biology. 65:228–249. 10.1093/sysbio/syv080

- Zuckerkandl E., Pauling L. 1962. Molecular disease, evolution, and genetic heterogeneity. Horizons in Biochemistry.:189–225.