This tutorial uses functions implemented in the developmental branch dev_PoMo_SNP. To download and install RevBayes from source, please follow the instructions here.

Polymorphism-aware phylogenetic models

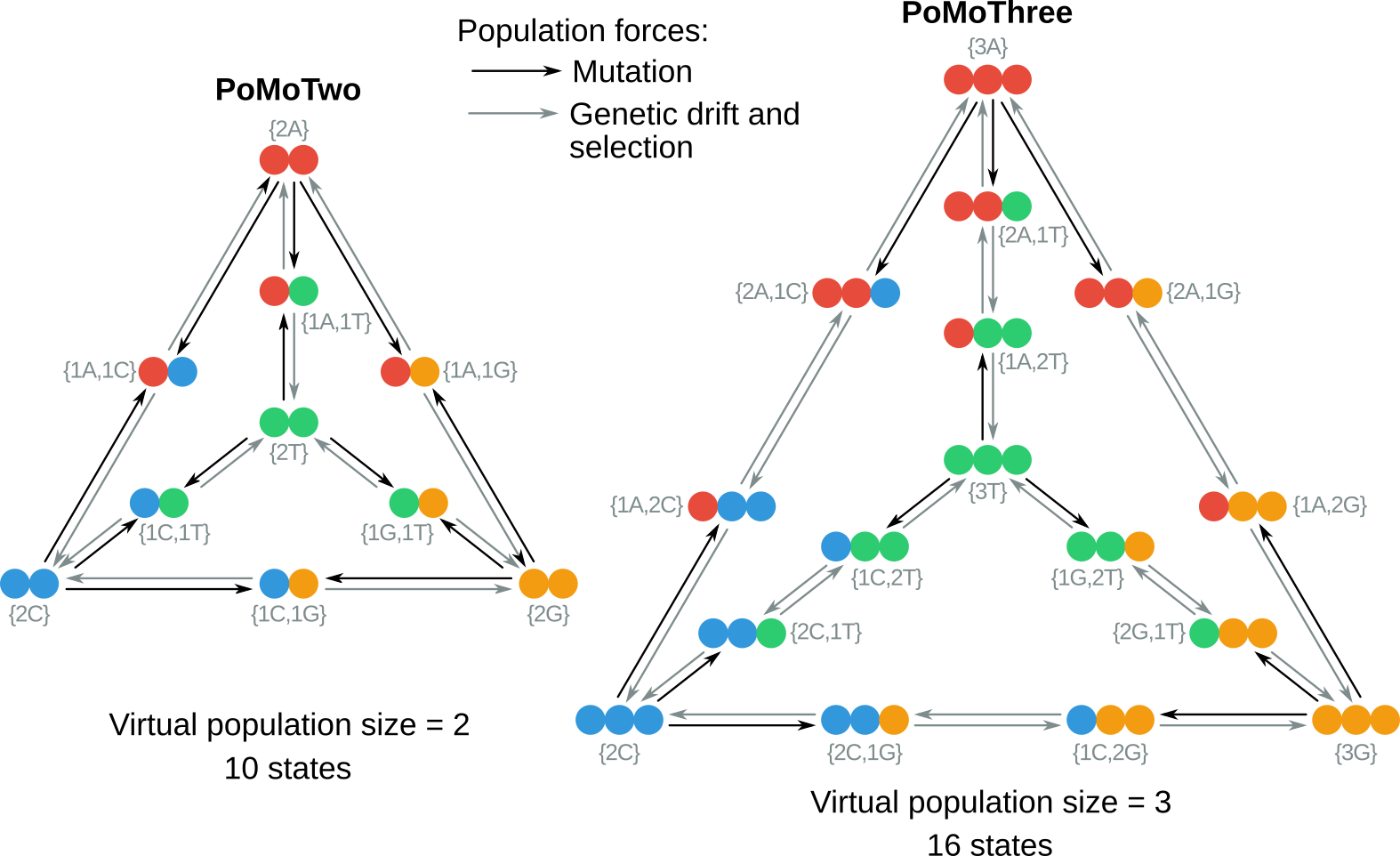

The polymorphism-aware phylogenetic models (PoMos) are alternative approaches to species tree estimation (De Maio et al. 2013) that add a new layer of complexity to the standard substitution models by accounting for population-level forces to describe the process of sequence evolution (De Maio et al. 2015; Schrempf et al. 2016; Borges et al. 2019). PoMos model the evolution of a population of individuals in which changes in allele content (e.g., due to mutations) and frequency (e.g., due to genetic drift or selection) are both possible ().

PoMos stand out from the standard phylogenetic substitution models and other species tree methods because they:

- allow to disentangle the contribution of evolutionary forces to the evolutionary process (e.g., genetic drift, mutational biases, and selection);

- consider polymorphisms, thus permitting inferences with data from multiple individuals and populations;

- naturally account for incomplete lineage sorting (i.e., the persistence of ancestral polymorphisms during speciation events), a known source of phylogenetic discord;

- are computationally efficient by directly estimate the species tree, thus circumventing the many constraints between the species tree and the genealogical histories.

Overall, PoMos constitute a full-likelihood yet computationally efficient approach to species tree inference. PoMos are designed to cope with recent radiations, including incomplete lineage sorting, and long divergence times.

Polymorphism-aware phylogenetic models: the model

PoMos model the evolution of a population of $N$ individuals and $K$ alleles in which changes in allele content and frequency occur. These are mediated by population forces such as mutation, genetic drift, and selection. The PoMo state-space includes fixed (or boundary) states \(\{Na_i\}\), in which all $N$ individuals have the same allele \(i \in \{0,1,...,K-1\}\), and polymorphic states \(\{na_i,(N-n)a_j\}\), in which two alleles $a_i$ and $a_j$ are present in the population with absolute frequencies $n$ and $N-n$.

- Mutations occur at a rate of $\mu_{a_ia_j}$. Mutations govern the allele content and only occur in the fixed states: \(q_{\{Na_i\} \rightarrow \{(N-1)a_i,1a_j\}}=\mu_{a_ia_j} \label{equation1}\tag{1}\) Often, a reversible mutational model is considered. In this case, we break the mutations into a base composition $\pi$ and an exchangeability parameter $\rho$ (i.e., $\mu_{a_ia_j}=\rho_{a_ia_j}\pi_{a_j}$) just like the GTR. However, in PoMos, these do not represent substitutions but mutations. Such an assumption can still model mutational biases quite well and simplifies obtaining formal quantities with PoMos. Another assumption of PoMos is that mutations can only occur in fixed states. This corresponds to the assumption that mutation rates are low, which is verified for the majority of multicellular eukaryotes.

- Genetic drift is modeled according to the Moran model, in which one individual is chosen to die and one individual is chosen to reproduce at each time step. Selection acts to (dis)favor alleles by differentiated fitnesses: $\phi_{a_i}$. Together, genetic drift and selection govern the allele frequency changes: \(q_{\{na_i,(N-n)a_j\} \rightarrow \{(n+1)a_i,(N-n-1)a_j\}}=\frac{n(N-n)}{N}\phi_{a_i} \label{equation2}\tag{2}\)

Like the standard substitution models, PoMos are continuous-time Markov models and are fully characterized by their rate matrices. The rates in \ref{equation1} and \ref{equation2} define the PoMos rate matrices. RevBayes includes the fnPoMoKN rate matrices that permit modeling population dynamics with any number of alleles, reversible mutations (i.e., $\mu_{a_ia_j}=\rho_{a_ia_j}\pi_{a_j}$) and selection. You can check the input parameters of this function by typing its name right after the question mark: ?fnPoMoKN.

Arguments

K : Number of alleles

Type: Natural, <any>, value

V : Number of virtual individuals

Type: Natural, <any>, value

N : Number of effective individuals

Type: RealPos, <any>, const reference

Default: NULL

mu : Vector of mutation rates: mu=(mu_a0a1,mu_a1a0,mu_a0a2,mu_a2a0,...)

Type: RealPos[], <any>, const reference

phi : Vector of fitness coefficients: phi=(phi_0,phi_1,...,phi_ak)

Type: RealPos[], <any>, const reference

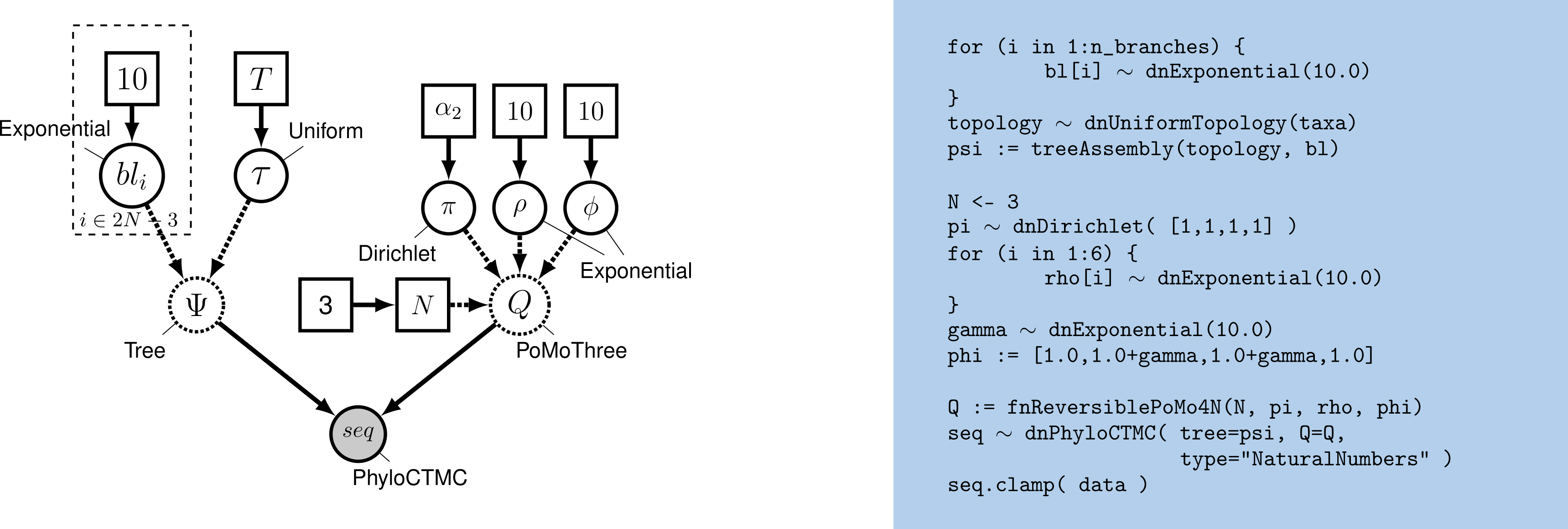

This tutorial demonstrates how to set up and perform analyses using polymorphism-aware phylogenetic models. You will perform phylogeny inference using the virtual PoMo Three. We will do this by setting the number of virtual (and effective) individuals to 3. These models allow for very efficient species tree inferences under selection because they operate on a small state space (missing reference). You will perform a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis to estimate phylogeny and other model parameters. By the end of this tutorial, we leave as an exercise to run the neutral version (PoMoTwo) and compare the resulting trees. The graphical model representation under PoMoThree is depicted in figure .

Count files

PoMos perform inferences based on allele frequency data, which is stored in count files. These files contain two header lines. The first line indicates the number of taxa and the number of sites (or loci) in the sequence alignment. You might have noticed that NPOP stands for the number of populations, but this is not necessarily the case. PoMos can be used to infer the evolutionary history of different species or even other systematic units of interest, such as species, subspecies, communities, and so forth.

The second line specifies the genomic position of each locus (chromosome and location) and the taxon names. The first two columns are not used for inference, so if you’re working with taxa for which this information is unavailable, you can input these columns with dummy values (e.g., NA or ?). The remaining lines the other lines in the count file include allelic counts separated by commas. All elements in the count file are separated by white spaces. Here is an example of some lines from the great ape count file we will analyze in this tutorial:

COUNTSFILE NPOP 3 NSITES 5

CHROM POS Gorilla_beringei_graueri Gorilla_gorilla_dielhi Gorilla_gorilla_gorilla

chr1 41275799 6,0,0,0 2,0,0,0 54,0,0,0

chr2 120104878 6,0,0,0 2,0,0,0 54,0,0,0

chr11 61364549 0,6,0,0 0,2,0,0 0,54,0,0

chr17 44837427 6,0,0,0 2,0,0,0 54,0,0,0

chr19 7495905 4,0,2,0 2,0,0,0 10,0,44,0

The four allelic counts in this count file represent the allelic counts of the A, C, G, and T, respectively. Therefore, we know that the Gorilla_gorilla_gorilla has an AG polymorphism at position 7 495 905 on chromosome 19. The order of alleles in the allelic counts can vary, but it is important to remember that the vectors of mutation rates, exchangeabilities, base frequencies, and fitness coefficients all follow the order of the allele counts in the count file:

- the base frequencies and the fitness vectors are in the same order as in the counts: i.e., \(\{a_0,a_1,\dots,a_{K-1}\}\);

- the mutation rate vector is \(\{a_0a_1, a_1a_0, a_0a_2, a_2a_0,\dots\}\);

- the exchangeability vector follows a similar pattern as for the mutation rates, but without the reversed mutation: i.e., \(\{a_0a_1, a_0a_2, \dots\}\).

Loading the data

The first step in this tutorial is to convert the allelic counts into PoMo states. Open the terminal and navigate to your working directory, which we will call PoMos (but you can choose any name you prefer). Inside PoMos, create the usual data and output folders. Before loading the data, run RevBayes by typing ./rb (or ./rb-mpi) in the console. Open the great_apes_pomothree.Rev file using a suitable text editor so you can follow what each command is doing. Once you understand the .Rev script in detail, you can run it automatically as follows:

./rb great_apes_pomothree.Rev

As mentioned earlier, the PoMo state space includes both fixed and polymorphic population states. However, allele counts are typically sampled from a small number of individuals. For example, sampled fixed sites may not actually be fixed in the original population. It is possible that we only sampled individuals with the same allele from polymorphic locus, leading to an inaccurate representation of the population’s true genetic diversity. The fewer individuals sampled, or the rarer the allele in the original population (e.g., singletons or doubletons), the more likely we are to observe false fixed sites in the sequence alignment.

There are methods that help us correct for this bias by attributing to each of the allelic counts an appropriate PoMo state. One such method is the weighted-method (Schrempf et al. 2016), which weights each PoMo state based on binomial sampling. In RevBayes, this is done automatically when we use the readPoMoCountFile function and set the weighting to Binomial. Alternatively, you can assign the PoMo state closest to the observed frequency. This method is called Fixed. In this tutorial, we will use Fixed. To use the readPoMoCountFile function, define the location of the counts file, set the virtual population size (which we set to 3, as we are using the virtual PoMo Three), specify the data type format PoMo and apply the Fixed correction as shown below:

N <- 3

data <- readPoMoCountFile(countFile="data/great_apes_1000.cf", virtualPopulationSize=N, format="PoMo", samplingCorrection="Fixed")

Information about the alignment can be obtained by typing data.

>data

PoMo character matrix with 12 taxa and 1000 characters

======================================================

Origination:

Number of taxa: 12

Number of included taxa: 12

Number of characters: 1000

Number of included characters: 1000

Datatype: PoMo

If, instead of a count file, you have a list of sequences per individual (in either fasta or nexus format), RevBayes can still convert it to PoMo data format. To do this, you need to read the sequences, provide a file with the taxon names, and perform the conversion to PoMo state space using pomoStateConvert. Please ensure that individual sequences belonging to the same taxon have the same name. Here are the commands you will need:

data_char = readDiscreteCharacterData("data/individual_sequences.nex")

taxa = readTaxonData("data/taxon_names.txt")

data = pomoStateConvert(aln=data_char, k=4, virtualNe=N, taxa)

Next, we define some useful variables. These include the number of taxa, taxa names, and the number of branches, which will be important for setting up our model in later steps.

n_taxa <- data.ntaxa()

n_branches <- 2*n_taxa-3

taxa <- data.taxa()

Additionally, we will set up a variable that holds all the moves and monitors for our analysis. Recall that moves are algorithms used to propose new parameter values during the MCMC simulation, while monitors print the values of model parameters to the screen and/or log files during the MCMC analysis.

moves = VectorMoves()

monitors = VectorMonitors()

Setting up the model

Estimating an unrooted tree under the virtual PoMos requires specifying two main components:

- the PoMo model, which in our case is PoMoThree;

- the tree topology and branch lengths.

A given PoMo model is defined by its corresponding instantaneous rate matrix, Q which depends on the virtual population size N, the mutation rates, assumed to be reversible and dependent on the allele frequencies pi, and the exchangeabilities rho. PoMoThree additionally includes allele fitnesses phi, as it accounts for selection. We will set up the virtual PoMoThree using the function fnPoMoKN. In particular, we set N to 3. Note that N is a fixed node, as we had previously defined.

Since pi, rho, and gamma are stochastic variables, we must specify a move to propose updates to them. A good move for variables drawn from a Dirichlet distribution (i.e., pi) is the mvBetaSimplex move. This move randomly selects an element from the allele frequency vector pi, proposes a new value drawn from a beta distribution, and then rescales all values to sum to 1. The weight option inside the moves specifies how often the move will be applied, either on average per iteration or relative to all other moves.

# allele frequencies

pi_prior <- [1,1,1,1]

pi ~ dnDirichlet(pi_prior)

moves.append( mvBetaSimplex(pi, weight=2) )

The rho and phi parameters must be positive real numbers and a natural choice for their prior distributions is the exponential distribution. Again, we need to specify a move for these stochastic variables, and a simple scaling move, mvScale, typically works. In this tutorial, we want our model to capture the effect of GC-bias gene conversion. For that, we define gamma, the GC-bias rate. The allele fitnesses phi for G and C will be represented by gamma, while those for A and T by 1.0. Note that phi is a deterministic node that depends on the GC-bias rate gamma.

# exchangeabilities

for (i in 1:6){

rho[i] ~ dnExponential(10.0)

moves.append(mvScale( rho[i], weight=2 ))

}

# fitness coefficients

gamma ~ dnExponential(1.0)

moves.append(mvScale( gamma, weight=2 ))

phi := [1.0,1.0+gamma,1.0+gamma,1.0]

Because we want the mutations to be reversible, we build the mutation rate vector as a deterministic variable depending on pi and rho:

# mutation rates

K <- 4

mu := fnPoMoReversibleMutationRates(K,pi,rho)

Alternatively, if we wanted to define a nonreversible mutation rate vector, we could have set mu directly, similar to how we set rho.

The function fnPoMoKN will create an instantaneous rate matrix. This function requires that an effective population size be input, but in most cases, you will not know it. Therefore, simply set it to the virtual population size.

# rate matrix

Q := fnPoMoKN(K,N,N,mu,phi)

The tree topology and branch lengths are stochastic nodes in our phylogenetic model. We will assume that all possible labeled, unrooted tree topologies have equal probability. For an unrooted tree topology, we use the nearest-neighbor interchange move mvNNI (a subtree-prune and regrafting move mvSPR could also be used).

# topology

topology ~ dnUniformTopology(taxa)

moves.append( mvNNI(topology, weight=2*n_taxa) )

Next, we create a stochastic node representing the length of each of the 2*n_taxa−3 branches in our tree. We can use a “for” loop to create a vector of branch lengths and assign a move to it.

# branch lengths

for (i in 1:n_branches) {

branch_lengths[i] ~ dnExponential(10.0)

moves.append( mvScale(branch_lengths[i]) )

}

Finally, we combine the tree topology and branch lengths using the treeAssembly function, which applies the value of the ith member of the branch_lengths vector to the branch leading to the ith node in the topology. Thus, the psi variable is a deterministic node:

psi := treeAssembly(topology, branch_lengths)

We have now fully specified all of the parameters of our phylogenetic model:

- the tree with branch lengths

psi; - the PoMo instantaneous rate matrix

Q; - the type of character data: i.e.,

PoMo.

Collectively, these parameters comprise a distribution called the phylogenetic continuous-time Markov chain, and we use the dnPhyloCTMC function to create this node. This distribution requires several input arguments:

sequences ~ dnPhyloCTMC(psi,Q=Q,type="PoMo")

Once the PhyloCTMC model is created, we can attach our sequence data to the tip nodes of the tree. Although we assume that our sequence data are random variables, they are realizations of our phylogenetic model. For inference, we assume that the sequence data are clamped to their observed values.

sequences.clamp(data)

When this function is called, RevBayes sets each of the stochastic nodes representing the tree’s tips to the corresponding nucleotide sequence in the alignment, indicating that those sequences have been observed.

Finally, we wrap the entire model in a single object. To do this, we simply pass model function one of the nodes previously defined.

pomo_model = model(pi)

Setting, running, and summarizing the MCMC simulation

For our MCMC analysis, we need to set up a vector of monitors to record the states of our Markov chain. First, we will initialize the model monitor using the mnModel function. This creates a monitor variable that will output the states for all model parameters when passed into an MCMC function. We will sample every 10th generation, and the resulting file will be found in the output folder.

monitors.append( mnModel(filename="output/great_apes_pomothree.log", printgen=10) )

The mnFile monitor will record the states for only the parameters passed as arguments. We use this monitor to specify the output for our sampled trees and branch lengths. Again, we sample every 10th generation.

monitors.append( mnFile(filename="output/great_apes_pomothree.trees", printgen=10, psi) )

Next, we create a screen monitor that will report the states of specified variables to the screen using mnScreen. This monitor helps us track the progress of the MCMC run.

monitors.append( mnScreen(printgen=10) )

With a fully specified model, a set of monitors, and a set of moves, we can now set up the MCMC algorithm that will sample parameter values in proportion to their posterior probability. The mcmc function will create our MCMC object. Additionally, we will perform two independent MCMC runs to ensure proper convergence and mixing.

pomo_mcmc = mcmc(pomo_model, monitors, moves, nruns=2, combine="mixed")

Now, we can start the MCMC run.

pomo_mcmc.run( generations=100000 )

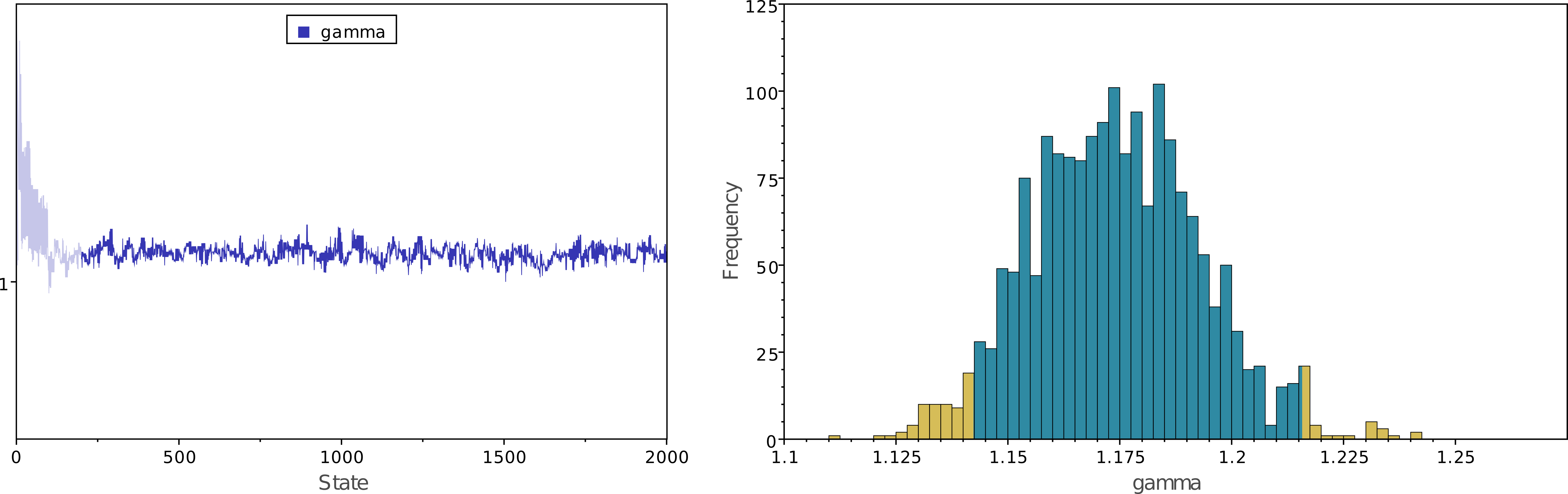

Once the analysis is complete, you will find the monitored files in your output directory. Software like Tracer allows you to evaluate convergence and mixing. Look at the file output/great_apes_pomothree.log in Tracer. There, you will see the posterior distribution of the continuous parameters. Let us examine the posterior distribution of the GC-bias rate $\gamma$. Is there any evidence of GC-bias in these great ape sequences?

In addition to continuous parameters, we also need to summarize the trees sampled from the posterior distribution. RevBayes can summarize the sampled trees by reading in the tree trace file:

trace = readTreeTrace("output/great_apes_pomothree.trees", treetype="non-clock", burnin= 0.2)

The mapTree function will summarize the tree samples and write the maximum a posteriori (MAP) tree to the specified file. The MAP tree can be found in the output folder.

mapTree(trace, file="output/great_apes_pomothree_MAP.tree" )

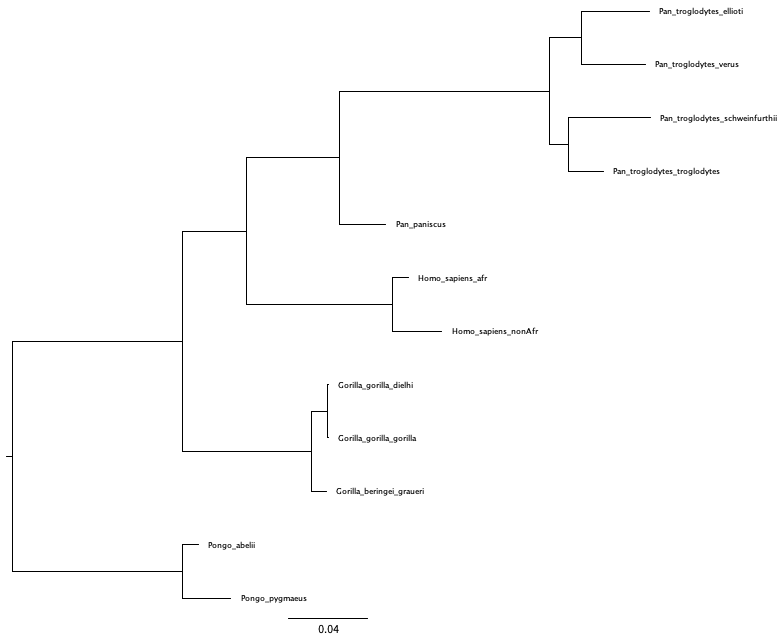

You can look at the file output/great_apes_pomothree_MAP.tree and open it in FigTree. The maximum a posteriori estimate of the great ape phylogeny under the PoMoThree model should look like that of .

We note that while visual inspection might be a good exercise to evaluate the convergence and mixing of the MCMC samples, quantitative methods exist and are recommended. These are implemented in R and ready to use; check tutorial Convergence assessment.

Some questions

-

What is the GC-bias rate (this is the selection coefficient) for the great ape populations? Rescale it to its real value by assuming the great apes have an effective population size of about 10 000 individuals. Use the relation $(1+\gamma’)^{N-1}=(1+\gamma)^{N_e-1}$ to rescale $\gamma$, where $N$ and $N_e$ represent the virtual and effective population sizes, and $\gamma’$ and $\gamma$ are the GC-bias rates for the virtual and effective populations.

-

Using as your guide, draw the probabilistic graphical model of the neutral PoMoTwo model.

-

What changes are necessary in the

great_apes_pomothree.Revfile to make inferences under the neutral PoMoTwo model? -

Run an MCMC analysis to estimate the posterior distribution under the PoMoTwo model. Are the resulting estimates of mutation rates (base frequencies and exchangeabilities) equal? If not, how much do they differ?

-

Compare the MAP trees estimated under PoMoTwo and PoMoThree. Are they equal? If not, how much do they differ?

- Borges R., Szöllősi G.J., Kosiol C. 2019. Quantifying GC-Biased Gene Conversion in Great Ape Genomes Using Polymorphism-Aware Models. Genetics. 212:1321–1336. 10.1534/genetics.119.302074

- Höhna S., Heath T.A., Boussau B., Landis M.J., Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. 2014. Probabilistic Graphical Model Representation in Phylogenetics. Systematic Biology. 63:753–771. 10.1093/sysbio/syu039

- Schrempf D., Minh B.Q., De Maio N., Haeseler A. von, Kosiol C. 2016. Reversible polymorphism-aware phylogenetic models and their application to tree inference. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 407:362–370. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.07.042

- De Maio N., Schlötterer C., Kosiol C. 2013. Linking great apes genome evolution across time scales using polymorphism-aware phylogenetic models. 30:2249–2262. 10.1093/molbev/mst131

- De Maio N., Schrempf D., Kosiol C. 2015. PoMo: An Allele Frequency-Based Approach for Species Tree Estimation. Systematic Biology. 64:1018–1031. 10.1093/sysbio/syv048